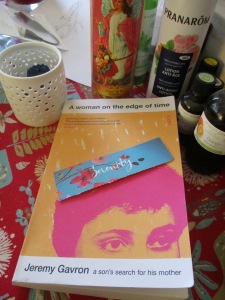

A Woman on the Edge of Time is a memoir that reads like a mystery, as Jeremy Gavron, a journalist, interviews family, old school friends, neighbours and colleagues of his mother Hannah Gavron, whom he has little memory of.

A Woman on the Edge of Time is a memoir that reads like a mystery, as Jeremy Gavron, a journalist, interviews family, old school friends, neighbours and colleagues of his mother Hannah Gavron, whom he has little memory of.

It documents his long-delayed search for a greater understanding of why she took her own life at 29 years of age, a married, working mother of two boys aged four and seven, living in Highgate, London.

It was 1965, she had been on the cusp of publishing a manuscript encapsulating the findings of her sociology research into the conflicts faced by young housebound mothers in North London, The Captive Wife. It was two years since another mother of two young children Sylvia Plath, had done the same thing.

Hannah Gavron was an out-going, confident child, an accomplished, confident teenager, popular and desirous of growing up. She wanted to do something with her life, to share her views with the world, but she also wanted freedom, to leave the constraints of family, to be in love, to claim her place in a rapidly changing society. She married at 18, went to RADA drama school for a year, quit, had two children, then realising her prospects were limited, went back to university to study sociology, attained a PhD and then a teaching post at the “iconic British art institute”, renowned for its experimental and progressive approach, Hornsey College of Art.

It seemed she had everything going for her, and yet at that tender age of 29, when her youngest son Jeremy, was 4 years old, she took her own life, shocking everyone around her.

Now the father of two girls himself, having previously just accepted the subject of his mother was a taboo subject never raised, he is seized by an urgency to know and understand the mystery, for how could it happen that a woman with so much going for her, two small children and a manuscript about to heighten her career, could suddenly end it all?

He interviews an extraordinary number of people and succeeds in recreating the jigsaw of Hannah’s life in incredible detail and begins to understand the multiple forces that may have played a part in leading up to that tragic decision.

As gripping as any mystery, it reads like a pageturner providing an interesting insight into the subject Hannah Gavron wrote her thesis about, ‘The Captive Wife’ and the struggle of women in the early 1960’s, a period just prior to the second wave of feminism, an era whose attitudes and dilemmas were encapsulated in Doris Lessing’s powerful account of a woman searching for her personal and political identity, The Golden Notebook, published in 1962.

Looking back from our own times, the subject seems an obvious one, still relevant today, but in 1960 it was neither obvious nor easy for her to get past her academic supervisors. For all the advances gained by the suffragette movement, and the opportunities the war had given woman to work and experience life beyond family, the woman’s movement was in retreat in the 1950’s and early 1960’s. in the post-war period, emphasis had been put on the role of motherhood in rebuilding Britain. The Beveridge Report, the basis for social reforms, spoke of how ‘housewives as mothers have vital work to do in ensuring the adequate continuance of the British race and of British ideals in the world’.

A woman attempting to forge an academic career in sociology at the time and proposing studies which focused on women as the subject, was provocative and a gesture not ready to be accepted by many in power in academia.

In Her Wake, Nancy Rappaport

It reminded me of reading Nancy Rappaport’s In Her Wake: A Child Psychiatrist Explores the Mystery of Her Mother’s Suicide, she too was 4 years old when her mother, who was raising a large family as well as being involved in organising society events and political campaigning, suddenly committed suicide. That drama took place in 1963 in Boston.

They are tragic stories and serve to create a more substantial memory for the authors, piecing together the lives of these woman who should have been able to contribute so much more than they did.

It left me wondering about the author himself, as he keeps himself well out of the narrative, not shining any light on how it had been for him to grow up under this shadow, this absence. How was it for him to accept the love of another mother, how might this turning point have influenced who he would become. Rather he shines his light outward and builds an incredibly detailed vision of his mother, leaving just a hint of suggestion that within her, we may also finds parts of him.

Further Reading

The Guardian, Nov 2015 – Jeremy Gavron: ‘My mother was a woman who looked for solutions. Suicide was a solution’

The Guardian, Apr 2009 – ‘Tell the Boys I Loved Them’

Buy a Copy of A Woman on the Edge of Time Here

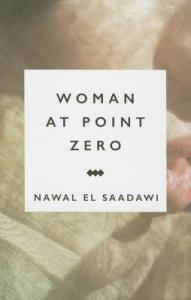

From her early days, Firdaus was a child who was noticed, though rarely looked out for, instances of cruelty and neglect made up the patchwork of her childhood. “Rescued” by an Uncle who’d already crossed filial boundaries, her one respite was to have been sent by him to school, his new wife further insisting she live there, perhaps the only paradisiacal period of her life, the one time she was left alone to flourish, to evolve, gaining her secondary school certificate, her sole prized possession.

From her early days, Firdaus was a child who was noticed, though rarely looked out for, instances of cruelty and neglect made up the patchwork of her childhood. “Rescued” by an Uncle who’d already crossed filial boundaries, her one respite was to have been sent by him to school, his new wife further insisting she live there, perhaps the only paradisiacal period of her life, the one time she was left alone to flourish, to evolve, gaining her secondary school certificate, her sole prized possession.

I learned that yesterday was World Book Day and when asked if I did anything to celebrate, I realised that I’d done something I’ve never done before in terms of reading, I finished my first Japanese Manga called ARTE, illustrated and written by Kei Ohkubo translated into French and set in Florence Italy!

I learned that yesterday was World Book Day and when asked if I did anything to celebrate, I realised that I’d done something I’ve never done before in terms of reading, I finished my first Japanese Manga called ARTE, illustrated and written by Kei Ohkubo translated into French and set in Florence Italy!