Fierce Appetites is my next read for Reading Ireland Month 2025, a nonfiction title I came across in 2022 when it was shortlisted for the Irish Book Awards Non Fiction Book of The Year. It didn’t win the award, that went to the excellent book I reviewed here, journalist Sally Hayden’s My Fourth Time We Drowned.

Lessons From My Year of Untamed Thinking

Fierce Appetites is a hybrid memoir, written over the year following the death of the author’s father, which gives her cause to reflect on their relationship, her childhood, her role as a parent/mother, her academic profession and some of the decisions she has made over the years, both the well thought out and the impulsive, those she takes some pride in and others she regrets.

The bonds between different members of a family are explored and pondered and found in the ancient texts.

The world has always been full of stepmothers, foster-mothers, fathers who do the ‘mothering’, aunts and cousins and grandparents who take on primary caring responsibilities, adoptive mothers, institutions that rear children (for better or worse), and innumerable kinds of almost-mothers, surrogate mothers, ‘they-were-like-a-mother-to-me’s. I was reared by a stepmother who mothered me as best she could, even when I sometimes believed she was like the mythic wicked stepmother from a fairy tale, and treated her accordingly.

Writings of the Past

Alongside the memoir aspect, written in 12 chapters, months of the years, her reflections lead into a potted introduction to medieval literature, each chapter finding some connection between the personal narrative and something of the medieval history/literature texts that she is reminded of. In fact each chapter is an essay, but I read it more as an interconnected text.

There is a popular misconception that people in the Middle Ages didn’t grieve as much or as deeply as we do today. Perhaps because of the extremely high rates of infant mortality, and images in modern culture of the Middle Ages as a time of endemic warfare, people tend to think that societies became numbed to death. But the medieval literature of grief disproves that claim. People suffered from the loss of their loved ones then just as much as we do now.

Most of this was unfamiliar to me, as it would be to most people unless you had studied it in university, but that was what initially piqued my interest in the book and I found it fascinating to read about all these references and the translations of those texts and how the author demonstrates how they have something relevant to say today if you care to sit with them and interpret/reflect on their meaning or find a connection, which Elizabeth Boyle does so brilliantly.

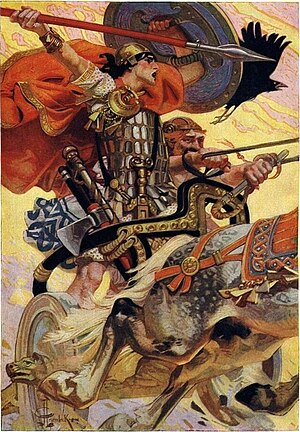

The things we fight for, and the reasons we fight for them, can be so elusive, so futile, and yet so deeply felt. Every year, I try to explain the emotional complexities of The Táin: From the Irish Epic Táin Bó Cúailnge to a new generation of students: Fer Diad and Cú Chulainn, fighting on opposite sides of a conflict and yet deeply bound by love for each other; Fergus’s divided loyalties; Medb’s myopic willingness to sacrifice her daughter for the sake of a bull.

They tell us through their stories and poems, how people lived, loved, coped and the scale of their imagination, and we reflect on how much things have or haven’t changed. Boyle not only shares her losses, she shares her excesses, yet this is not a transformational memoir, it is raw and unashamedly wicked, just like some of the characters in those ancient texts.

At the mortuary, we had been handed a NHS leaflet on dealing with grief. One of its sensible pieces of advice is not to make any major life changes in the first year of losing someone close to you. In medieval literature, characters are not given self-help pamphlets. When they suffer grief, they destroy mountains, raze kingdoms, tear their hair out and scorch the earth. I just sat numbly at the kitchen table, drinking gin and sending unwise WhatsApp messages to ex-lovers.

History Repeats

The book was written in 2020, which is also interesting because it was a year that gave many the opportunity to pursue projects like this, and also because of the political climate that gets occasionally referenced.

While Boyle lives in Ireland, she often travels to the UK to see her daughter and abroad to speak on her subject of expertise.

One of the main objections to travel in the Middle Ages was that it led to sin.

When she mentions the political situation, she does so from the point of view of a historian, and these points made from five years ago are interesting to reconsider today.

History is full of incremental improvements and revolutionary convulsions – often these are followed by reactionary backlashes in which rights are revoked, inequalities re-established.

There are so many interesting insights and observations, challenges and meandering trains of thought, I highlighted so many and could easily have spent many more hours looking up the references.

Highly Recommended, if you are curious about medieval literature and balancing family, career and personal interests.

Author, Elizabeth Boyle

Elizabeth Boyle was born in Dublin, grew up in Suffolk and returned to live in Dublin in 2013. She is a medieval historian specialising in the intellectual, literary and religious culture of Ireland and Britain. A former Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Cambridge, she now works in the Department of Early Irish at Maynooth University, where she was Head of Department for five years until 2020.

Fierce Appetites is her debut collection of personal essays and was shortlisted for the Irish Book Awards Non Fiction Book of the Year 2022.

Minor Feelings is a collection of creative nonfiction essays that invites the reader to view aspects of the life experience of artist and writer Cathy Park Hong, from a little observed and known viewpoint, that of an Asian American woman pursuing her own authentic form of expression, while looking for other role models, disrupting the silence that is expected, through a polemic on race, ethnic origins and art.

Minor Feelings is a collection of creative nonfiction essays that invites the reader to view aspects of the life experience of artist and writer Cathy Park Hong, from a little observed and known viewpoint, that of an Asian American woman pursuing her own authentic form of expression, while looking for other role models, disrupting the silence that is expected, through a polemic on race, ethnic origins and art.

A tribute to thirty one year old artist and poet

A tribute to thirty one year old artist and poet  The slim autobiography shares stories from her childhood up to the age of 23, all of it taking place in South Africa. In her early years, as was customary among amaXhosa people, she lived with her grandparents. It was often the case while parents were trying to earn a living in starting a new life, that the extended family and home community was the safest, most caring environment for young children to be. There was always someone to look after children, they had food, shelter, company and they thrived.

The slim autobiography shares stories from her childhood up to the age of 23, all of it taking place in South Africa. In her early years, as was customary among amaXhosa people, she lived with her grandparents. It was often the case while parents were trying to earn a living in starting a new life, that the extended family and home community was the safest, most caring environment for young children to be. There was always someone to look after children, they had food, shelter, company and they thrived.

Magona was born in 1943 in the small town of Gungululu near Mthatha, in what was then known as the homeland of Transkei, in the Eastern Cape of South Africa.

Magona was born in 1943 in the small town of Gungululu near Mthatha, in what was then known as the homeland of Transkei, in the Eastern Cape of South Africa.