It has been twenty years since Kiran Desai published her Booker Prize winning The Inheritance of Loss, so this latest novel has been much anticipated by many.

It was one of two Booker shortlisted novels this year that I was interested to read, because of their cross-cultural settings, the other being Flashlight by Susan Choi, set in Japan, US and North Korea.

Character led New Generation Indian Drama

At 670 pages, I had to be sure about Desai’s novel before committing to read it, an immersive Indian family saga sounded promising, then the author’s intention to write ‘a present-day romance with an old-fashioned beauty’ sealed it for me.

It was everything I hoped and more. All the old fashioned values and dilemmas of an India of the past and then the mix of young people sent abroad for an American education, isolated from their home culture and influences, while both benefiting from, and coping with the effect of a western education and so-called freedoms as they try to find their place in the world.

We also bear witness to the imbalance in power in a co-dependent and coercive relationship of a manipulative and emotionally abusive man over a young woman, who struggles to see what is happening to her and yet knows it is not right.

The Loneliness of Winter in a Foreign Country

In this modern day Indian family chronicle, we meet aspiring novelist, freelance writer Sonia in the snowy mountains of Vermont, and Sunny a struggling journalist now in New York.

Unable to return home during the holidays, having been in America for three years and not returned to India for two, Sonia complains to her family.

“Lonely? Lonely?”

In Allahabad they had no patience with loneliness. They might have felt the loneliness of being misunderstood; they might know the sucked-dead feeling of Allahabad afternoons, a tide drawn out perhaps, never to return, which was a kind of loneliness: but they had never slept in a house alone, never eaten a meal alone, never lived in a place where they were unknown, never woken without a cook bringing tea or wishing good morning to several individuals.

In Vermont working on campus in the library over the two month winter closure, with two foreign students, one day she encounters a much older man Ilan de Toorjen Foss, who invites her to dine, promises to find an internship for her. He takes something from her that becomes one of the core threads of the story, the thing that will bring Sonia and Sunny’s fates full circle.

Her colleagues in the library are suspicious.

“I still don’t understand who this person is and why he is here in the dead of winter. It doesn’t add up. Where is his family?”

The Jealous Confused Girlfriend

When Sunny’s American girlfriend Ulla opens a letter from his mother with a photo of Sonia inside, he tries to downplay the foreign custom it refers to. She is suspicious.

“There’s nothing sinister about the letter,” he said. “Everyone gets these at my age, forwarded by relatives, friends, people who’ve never set eyes on you – a great pile arrives when you finish college, and the flood continues until everyone is settled. Then there is a lull before they begin marrying off the progeny of these mishaps, each generation lesser than what came before, because what hope can you have from such a process?”

Sunny avoids answering his mother’s calls and now his girlfriend suspects this custom might be the real reason he is reluctant to tell his family about their relationship. He finds it increasingly difficult to navigate his relationship, discovering there are as many pressures and expectations, with little understanding of the rules. He seeks an escape.

An Arranged Marriage? Not Likely!

Neither Sonia or Sunny are thinking about marriage according to the cultural traditions of their parents generation; they are too swept up dealing with their current circumstances. The letters they received were a response to a letter in India, sent from one family to the other, suggesting a match, inferring but never outright stating, a kind of favour that might balance out an old grievance these families had faced a decade ago, after an investment turned sour.

It was essential to remain close to those who had caused you harm so that the ghost of guilt might breathe through their dreams, that their guilt might slowly mature to its fullest potential. Not that Dadaji had thought it through – it never worked to consciously plot, to crudely calculate – and he himself was astonished at the possibility of what was unfolding. Even now it would never do to name this liability. The Colonel would not allow his grandson to bear the burden of his grandfather’s mistake. Dadji and Ba may simply suggest a desirable match between the grandchildren, two America-educated individuals, two equals, two people who naturally belonged together because of where they came from and where they were going. Without either of them mentioning it, the obligation might be beautifully unravelled.

The intended match fizzles out without Sonia or Sunny meeting, neither are interested, both already in romantic connections they are attached to but not entirely happy in.

However their paths will cross, igniting intrigue, but again they separate, as they struggle to find their place in the world and in themselves and overcome the mistakes they have made on the way, which have nothing to do with each other.

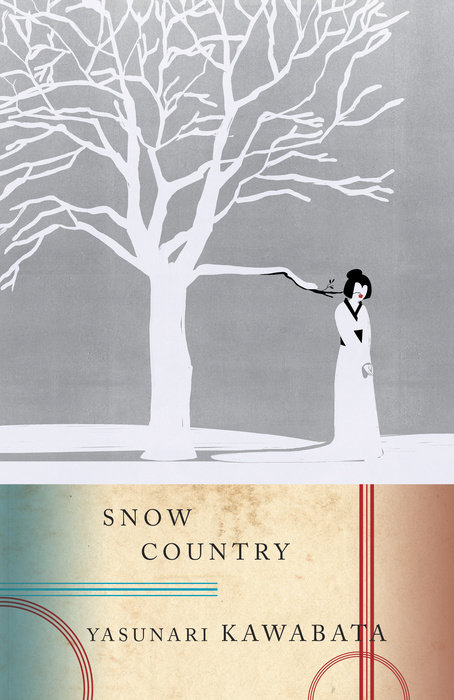

He passed a young woman sitting cross-legged staring at the rain. By her side was a book. Because Sunny couldn’t abide passing a book whose title he could not read, he walked by again and saw she had a face planed like a leopard, long lips, and watchful eyes, hair in a single oiled braid, but he still couldn’t see the title. So he passed by again. And one more time before he detected it: Snow Country by Kawabata.

Ultimately the two young people flee their present and go into a period of self imposed reflection, Sonia retreating to her mother’s house in the mountains, where she has mystical revelations that she decides not to be frightened of, but to look for simpler meaning from; while Sunny finds solace in nature and human rhythms in a village on the coast of Mexico, blending in with locals and receiving a visit from his friend Satya who is having his own realisations, seeking apology and reconciliation.

There is so much to navigate and nothing mentioned gives anything away, just an idea of the journey these two will go on as they seek a solution to their loneliness, a confrontation with themselves, in various parts of the world.

A Cultural Coming of Age Youth’s Journeying

I was hoping for an immersive, character led Indian novel and this was everything I hoped for and more. It had all the old fashioned values and dilemmas of an India of the past and then the interesting blend of young people sent abroad for an education, isolated from their culture and influences, experimenting with the new and forbidden, benefiting from and coping with the effect of a western education and freedoms, while trying to understand themselves and their place in the world.

Though there were aspects that were deeply troubling, like the grooming of a young foreign student by a much older man, they are sadly relevant to the situation an isolated young woman without family around, might encounter abroad.

At the same time there were generational threads and mystical elements that disturb the equilibrium; there are parasitic entities met on their paths that cause them to learn, to suffer and grow, requiring surrender and courage. Everyone, young and old alike, must deal with their situation in order for any kind of balance to be regained.

I found the novel thoroughly entertaining and engaging, the mix of traditional and contemporary attitudes, the facing up to change and resistance against old roles. To a certain extent, as outsiders to the culture, we rely on authors to represent it authentically, but here we have characters that have been influenced and educated outside their own culture from within privileged families, which makes them neither one thing nor the other.

Loved all of it, did not want it to end, the ending was perfect.

Further Reading

Book Extract: An extract from The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny by Kiran Desai

NPR Review: ‘The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny’ is a terrific, tangled love story by Maureen Corrigan

Kiran Desai, Author

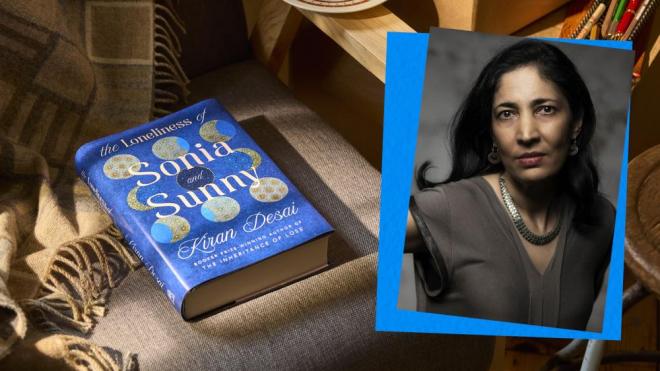

Kiran Desai was born in New Delhi, India, was educated in India, England and the United States, and now lives in New York.

She is the author of Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard, which was published to unanimous acclaim in over 22 countries, and The Inheritance of Loss, which won the Booker Prize in 2006, as well as the National Book Critics Circle Award, and was shortlisted for the Orange Broadband Prize for Fiction. Her third novel, The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2025.

In 2015, the Economic Times listed her as one of 20 most influential global Indian women.

In the past of my parents, and certainly my grandparents, an Indian love story would mostly be rooted in one community, one class, one religion, and often also one place. But a love story in today’s globalised world would likely wander in so many different directions. My characters consider: Why this person? Why not as easily someone else? Why here, not there? In the past people were always where they had to be. My indecisive lovers, Sonia and Sunny, meet and part across Europe, India and America, their idea of themselves turning ever more fluid.