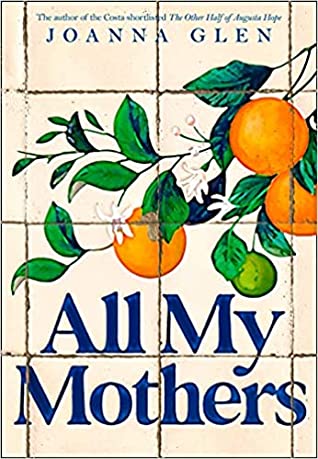

I picked this book up because of its premise of a child having questions about her early life and origins, sensing she is being lied to by her parents.

A 30 Year Story from 80’s London to Córdoba

The book is 480 pages and most of the first half is narrated by Eva as a child or teenager. It begins as she is starting school and beginning to develop friendships. She befriends Bridget Blume and is besotted. Not just by her, but by her entire family, especially her mother who is so unlike Eva’s mother whom she calls Cherie (like her father does).

At school Eva is deeply affected by a book the teacher reads ‘The Rainbow Rained Us’, in which a rabbit throws a stone at the rainbow of Noah’s Ark breaking it apart into hundreds of multicoloured mothers who repopulate the earth with children.

The Many Colours of Mother Love

There Blue Mother stood in a mesmerising cornucopia of blues, at the edge of a turquoise sea, laughing, the wind in her hair, surrounded by her blue family.

‘Blue Mother is free and open and speaks from her heart.’

She sounded exactly like Bridget’s mother – utterly perfect.

From then on she refers to her mother as Pink Mother and Bridget’s mother as Blue Mother.

Pink Mother was sitting upright in a kind of fairy-tale bed, a bit like my mother and father’s, a four-poster, with a roof and curtainy droops around it.

No,no,no.

‘Pink Mother is delicate and feminine,’ said Miss Feast, explaining that delicate meant not strong.

When they are asked to share a baby photo, Eva becomes even more convinced than she already was, that her mother is not her mother, there is no photo of her as a baby, nothing before the age of three and a half.

The novel’s first half follows her through primary school, her developing friendship and first great loss, first the loss of a favourite teacher, then a death that will result in her friend’s family moving to another country and then abandonment by her father, who returns to Spain and rarely if ever makes contact.

Eva’s personality develops and is compromised by these losses and causes her to develop or accept superficial relationships, taking some time to realise what she lost by neglecting what has been meaningful to her.

Hispanic Studies, La Mezquita, A Headless Nun

In the second half of the novel she has started a university degree, changing locations due to the demands of her boyfriend Michael.

The pace really picks up in this half, perhaps because we have left the child narrator behind, so Eva becomes less introspective and more in charge of acting on the questions and thoughts she has and voicing some of the strong opinions she has.

When told they will spend a summer semester in Córdoba, Spain, the separation from all that is familiar and expected of her, marks the beginning of a transformation and a quest into looking for the answer to questions she has about her origins.

The second half is something of an adventure as she develops a new friend Carrie who is interested in helping her and the two begin to consider not returning to their previous lives, to stay in Córdoba.

As Eva enters her 20’s her relationships and perspective begin to evolve, although she remains somewhat detached, circumspect and emotionally distant. With the presence of those around her, she begins to understand the complexity of being a mother, of being mothered and that judgments can change, as can people, especially when they find those relationships that are mutually nurturing.

The final third of the jumps into a second person narrative perspective ‘you’ and becomes somewhat nostalgic and didn’t work quite so well as the preceding chapters. It’s like the beginnings of a letter to a little girl who is still a baby, perhaps the thing that she had missed from her own life, being provided for another.

Writing From Experience versus Imagination or Observation

It is an interesting and captivating read, however I couldn’t help but feel as I was reading that this was imagined, rather than felt, because I am interested in books, fiction or nonfiction that come from the experience of separation.

In an interview with Carolyn Ray of JourneyWoman Bookclub, Joanna Glen shared that one of her aims was to explore the question, What is Our Deepest Longing?

I suppose the motherhood theme came next thinking what is our deepest longing that we have right from the beginning and of course a baby’s deepest longing is to gaze into the mother’s eyes and receive the gaze of love back. So I was thinking, what would be the most powerful or perhaps the saddest lack, would be not to feel that connection. That would be a very visceral fundamental lack.

She shares more about her own experience in the interview, which was the opposite of what she explores in the novel regarding the mother child connection, but brings alive the adventure of living abroad, in the town of Córdoba as a young person.

Overall, an enjoyable summer read that is likely to spark an interest in Córdoba, if like me you have never been there and one that celebrates female friendship and connection across different age groups and cultural backgrounds.

Further Reading

TripFiction Review: All My Mothers by Joanna Glen, coming of age novel mainly set in Córdoba. Aug 2021

Author, Joanna Glen

Joanna Glen’s novels include All My Mothers and The Other Half of Augusta Hope, which was shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award and the Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award.

She and her husband live in Brighton.

Apart from being a brilliant, unputdownable read, I continuously referred back to that image on the cover with total pleasure trying to deduce which flower it was we were tracking down next.

Apart from being a brilliant, unputdownable read, I continuously referred back to that image on the cover with total pleasure trying to deduce which flower it was we were tracking down next.

Before reading Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire, I downloaded a translation of Antigone to read, she acknowledges herself that Anne Carson’s translation of Antigone (Oberon Books, 2015) and

Before reading Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire, I downloaded a translation of Antigone to read, she acknowledges herself that Anne Carson’s translation of Antigone (Oberon Books, 2015) and  “Stories are a kind of nourishment. We do need them, and the fact that the story of Antigone, a story about a girl who wants to honour the body of her dead brother, and why she does, keeps being told suggests that we do need this story, that it might be one of the ways that we make life and death meaningful, that it might be a way to help us understand life and death, and that there’s something nourishing in it, even though it is full of terrible and difficult things, a very dark story full of sadness.”

“Stories are a kind of nourishment. We do need them, and the fact that the story of Antigone, a story about a girl who wants to honour the body of her dead brother, and why she does, keeps being told suggests that we do need this story, that it might be one of the ways that we make life and death meaningful, that it might be a way to help us understand life and death, and that there’s something nourishing in it, even though it is full of terrible and difficult things, a very dark story full of sadness.” Kamila Shamsie was born in Karachi and now lives in London, a dual citizen of the UK and Pakistan. Her debut novel In The City by the Sea, written while still in college, was shortlisted for the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize in the UK and every novel since then has been highly acclaimed and shortlisted or won a literary prize, in 2013 she was included in the Granta list of 20 best young British writers.

Kamila Shamsie was born in Karachi and now lives in London, a dual citizen of the UK and Pakistan. Her debut novel In The City by the Sea, written while still in college, was shortlisted for the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize in the UK and every novel since then has been highly acclaimed and shortlisted or won a literary prize, in 2013 she was included in the Granta list of 20 best young British writers.