A new novel by Eowyn Ivey is like no other anticipated novel for me. I still remember the effect of reading her debut The Snow Child, my One Outstanding Read of 2012 and now with Black Woods, Blue Sky, she has created that magic again.

It is extraordinary.

No Madeleine in Sight

The title is a reference to this quote from Marcel Proust:

Now are the woods all black

but still the sky is blue

May you always see a blue sky overhead

my young friend

and then

even when the time comes

which is coming now for me

when the woods are black

when night is falling

you will be able to console yourself

as I am doing

by looking up to the sky.

A Nature vs Nurture Conundrum

On the cover, we see the blue sky and the black woods and an image of a standing bear, whose shadow is a man.

It is the story of troubled Birdie, her six year old daughter Emaleen and a reclusive character Arthur, who Birdie is entranced by. In the opening scene Birdie awakens with a hangover, goes off into the woods with a fishing line, leaving her daughter alone sleeping, forgetting to take her rifle.

The large more fearsome grizzly bears were rarely seen, leaving only paw prints or piles of scat in the woods. But now and then, a bear would surprise you. They were too smart to be entirely predictable.

This entire scene is a foreshadowing of the novel, of the attempt of a young, single mother to do right, who doesn’t have sufficient awareness of certain red lines she should not cross, which have nothing to do with the depth of love she has for her child and the determination to do better than how she was mothered.

Though she doesn’t yet know him that well, and despite his odd way of being and other clues that might make her question going off to be with him, she and her daughter depart for the cabin in the mountains where Arthur dwells, not realising they will be living off the grid.

Arthur has some strange tendencies that Birdie tries to understand. Emaleen understands more than her mother and is both sympathetic to him and afraid of him.

The Alaskan Wilderness, Beauty and Bears

The novel charts their relationship and brings the Akaskan landscape and botanical life alive, in all its beauty and bite.

The novel is told in three parts, each one introduced with a black and white pencil illustration of a native Alaskan plant, one that symbolically has something to say about what will pass.

It is also a study in the nature of the bear, of the similarity of some of their their instincts to humans.

A sow grizzly appeared to care for her cubs with the same tender exasperation as a human mother, and when threatened by a bear twice her size, she wouldn’t hesitate to put herself between the attacker and her offspring. She was the most formidable animal in all of the Alaska wilderness, a sow defending her cub.

In the Wilderness Pay Attention

While the initial period of their stay is encouraging, the signs of discontent are already present and like Icarus who flew too close to the sun, Birdie’s judgement is impaired.

It was impossible, what Birdie wanted. To go alone, to experience the world on her own terms. But also, to share it all with Emaleen.

In an attempt to try and appease Birdie, he suggests she takes a day to herself, to be free as she desires. All is well until she is lured by shrubs of blueberries that lead her off course, or was it when she stepped into a ring of mushrooms igniting an age-old curse.

Don’t you dare go blundering into it. That’s what Grandma Jo would say. Witches and fairies danced in a circle here on moonlit nights, the mushrooms sprouting up where their feet touched. If you trespassed inside the circle, they would punish you. You might be forced to dance away the rest of your life in the ring, or, if you escaped, the curse would follow you back home and weave mischief and sorrow through your days.

The novel has a strong element of suspense at the same time as it explores the effect of decisions made by adults on children, on the things that might be overcome and others that are unlikely to. Every character carries something that contributes to our understanding of the story and the responses of the little girl Emaleen highlight much that demands our attention.

Autobiographical Elements

Eowyn Ivey describes Black Woods, Blue Sky as her most personal yet and the most important story she has ever told, with Emaleen being the closest to an autobiographical character she has written. It is a story the author had been trying to figure out how to write her entire life, as she wrote into ‘the darkest fears and most magical memories of childhood’, while demonstrating how people’s choices have a ripple effect through time.

“…the little girl’s fear and sense of magic, the feeling she loves about being so far out in the wilderness of Alaska, but also the thing she is afraid of, that is all directly from me”

It is a heart-stopping, captivating read, unpredictable and nerve-wracking in parts and yet we are able to bear witness, knowing we are safe in the hands of an empathetic, nature loving author, whose authenticity and understanding of human nature resonate throughout the text. Just brilliant.

If you enjoyed The Snow Child, you will love this too. If you haven’t read Eowyn Ivey yet, you’re in for a treat.

Outstanding. Best of 2025.

Author, Eowyn Ivey

Eowyn Ivey is the author of The Snow Child, an international bestseller published in thirty countries, a Richard and Judy Bookclub pick, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and winner of a British Book Award.

Her second novel, To the Bright Edge of the World, was longlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award, shortlisted for the Edward Stanford Travel Writing Award, and was a Washington Post Notable Book.

A former bookseller and reporter, she was raised in and lives in Alaska.

Born in 1968, clearly intelligent and showing she had potential from a young age, ironically – getting married at the age of 19 was something of a rebellious act. Nineteen, an age of youthful idealism, where if not wary, we risk being fooled into taking the intensity of our feelings seriously and wind up wed. Or am I being just a tad cynical?

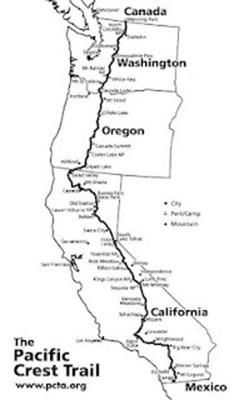

Born in 1968, clearly intelligent and showing she had potential from a young age, ironically – getting married at the age of 19 was something of a rebellious act. Nineteen, an age of youthful idealism, where if not wary, we risk being fooled into taking the intensity of our feelings seriously and wind up wed. Or am I being just a tad cynical? The death of her mother at 45, knocked her off her straight and wedded course setting her on a side road to self-destruction, though fortunately something inside, perhaps the ever-present loving spirit of her mother (and a few of her sensible genes) mapped out an escape route from her self-destructive self by planning to hike the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT).

The death of her mother at 45, knocked her off her straight and wedded course setting her on a side road to self-destruction, though fortunately something inside, perhaps the ever-present loving spirit of her mother (and a few of her sensible genes) mapped out an escape route from her self-destructive self by planning to hike the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT).

I recognise in the first two paragraphs the allure of melodic sentences, the promise of picturesque phrases that almost make music as they fly off the page like dancing quavers to craft pictures in my mind of that breath-taking, wild and unforgiving Alaskan landscape.

I recognise in the first two paragraphs the allure of melodic sentences, the promise of picturesque phrases that almost make music as they fly off the page like dancing quavers to craft pictures in my mind of that breath-taking, wild and unforgiving Alaskan landscape.