Soundings is a dual narrative memoir, that recounts two journeys a woman makes, pursuing her dream to see the grey whales that migrate up the coast from Mexico where her journey begins, to the northernmost Arctic town of Utqiagvik.

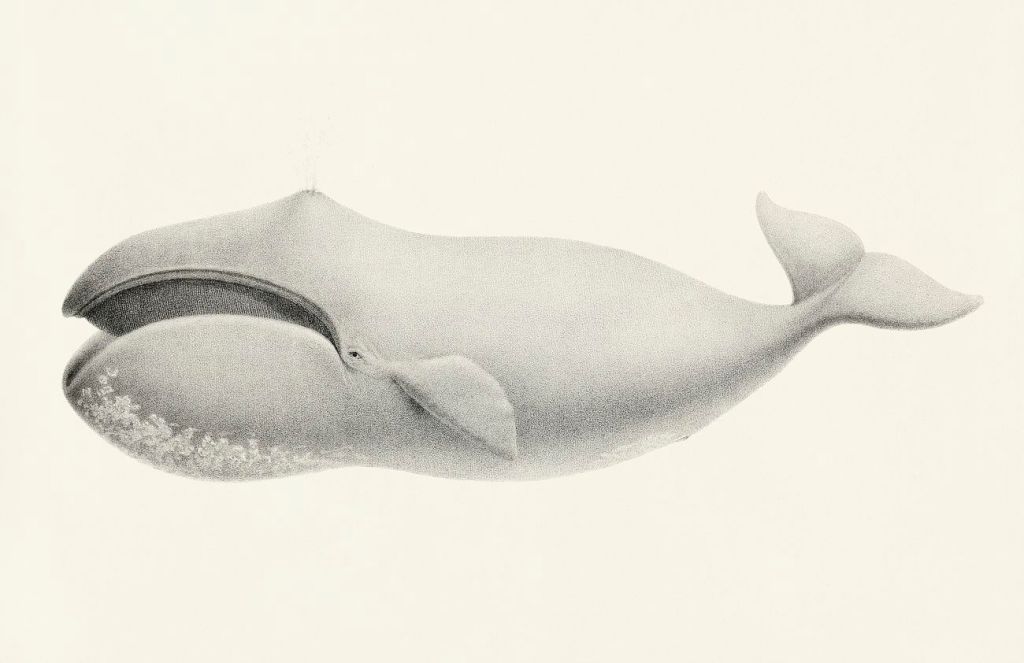

The Iñupiat have thrived there, in a place periodically engulfed in ice and darkness, for thousands of years, bound closely together by their ancient culture and their relationships with the animals they hunt, most notably the magnificent and mysterious bowhead whale. I hadn’t just seen the whales there, I’d joined a family hunting crew, travelling with them in a landscape of astonishing beauty and danger.

The book is structured so that each chapter alternates the twin journeys, the first one when she is a young BBC journalist on a sabbatical – the trip isn’t a job assignment, she is winging it, not knowing ahead of time where she might stay, or that she might join an indigenous whale hunt – to be in a position to observe the whales.

She is going there to listen, observe and with luck, participate.

The idea was that you could immerse yourself in a place and absorb more than if you were questioning people as a reporter and narrowing the world down into stories. I was supposed to take thinking time away from the relentless news cycle, open my mind and return bursting with creativity and new ideas.

The second trip is more of an escape from her current reality, that of a young single mother awarded sole custody, who can not afford to live in her home (due to high mortgage payments), reluctantly returned to her parents home in Jersey – who then decides she wants to make a return trip and provide her two-year-old son a formative experience of travel and whale watching.

I’d felt so alive then, so connected to other people and to the natural world. If only I could feel that way again and give that feeling to Max.

I recalled reading Scottish poet and nature essay writer Kathleen Jamie’s Surfacing, where she visits and brings alive an archaeological site Nunallaq, in the Yup’ik village in Quinhagak, Southern Alaska.

Doreen Cunnningham’s interest in whales and the environment inclines more towards the science, research and a personal desire for a sense of belonging and a large dose of wishful thinking, than the more poetic and philosophical Jamie, who went towards the tundra in search of surfaces that might reconnect us to the past. However, the two books together make informative and astonishing reading.

I told myself I would relearn from the whales how to mother, how to endure, how to live.

Beneath the surface, secretly, I longed to get back to northernmost Alaska, to the community who’d kept me safe in the harsh beauty of the Arctic and to Billy, the whale hunter who’d loved me.

Once you realise that the narrative goes back and forth, it becomes easier to stick with it, the chapters in the more recent past focus as much on the logistics of trying to travel with a child, car seat and stroller, finding kindred spirits who might assist getting her on a boat to see the whales, while doing her best to avoid those fellow travellers who look askance at a young mother, attempting the extraordinary.

As they travel, she also shares something of the challenges in the past of reporting on climate change, the reluctance to report on the environment and the habit many broadcasters had of always finding a sceptic to present an alternative view to the facts.

What was going on was that media all over the world had regularly been allowing sceptics o misrepresent science without adequately challenging them, and presenting them as though they carried equal scientific weight to mainstream climate researchers…This ‘insistence on bringing in dissident voices into what are in effect settled debates’ created what the report called ‘false balance’.

In her earlier visit, she takes time to listen to their stories, of the first ships that came in, bringing equipment, alcohol and disease. She hears of the social problems of another indigenous people, of children sent away, of PTSD, of a sense of rage and powerlessness, of a need to educate themselves in order to better represent and protect their culture and ways.

She also hears of the effect of the warming of the ocean first hand, its impact on animals, on the ice, on patterns of behaviours, of the risk to their livelihood and comes to understand the importance differences between a people who live in harmony with their environment and depend on it and those who came intent on exploiting it.

We also learn a little of her childhood experiences, of her wild pony Bramble, of an Irish granny and the songs she still sings that the whales seem to respond to. She injects enough of the personal story to keep the pace going, as the flow risks at times being overwhelmed by the facts and background research. However, as I go back and reread the passages I highlighted, I find it interesting to encounter some of this information a second time around, now that I’ve removed the expectation of a flowing narrative.

There is a something in this book for everyone, it defies genre and shows the gentle, yet vulnerable courage of a young mother persevering against the odds, seizing the reins of her life, following her intuition and going on a grand adventure with a small boy, who is perhaps more likely the greater teacher to her than the elusive whales, on motherhood.

Doreen Cunningham, Author

Doreen Cunningham is an Irish-British writer born in Wales. After studying engineering she worked briefly in climate related research at NERC and in storm modelling at Newcastle University, before turning to journalism. She worked for the BBC World Service for twenty years as an international news presenter, editor, producer and reporter.

She won the RSL Giles St Aubyn Award 2020 and was shortlisted for the Eccles Centre and Hay Festival Writers Award 2021 for Soundings, her first book.

The second volume of essays by Kathleen Jamie that I’ve read, more encounters with birds on lonely, windswept islands that have long been abandoned by humans, though traces remain of their earlier occupation.

The second volume of essays by Kathleen Jamie that I’ve read, more encounters with birds on lonely, windswept islands that have long been abandoned by humans, though traces remain of their earlier occupation.

The Hvalsalen

The Hvalsalen