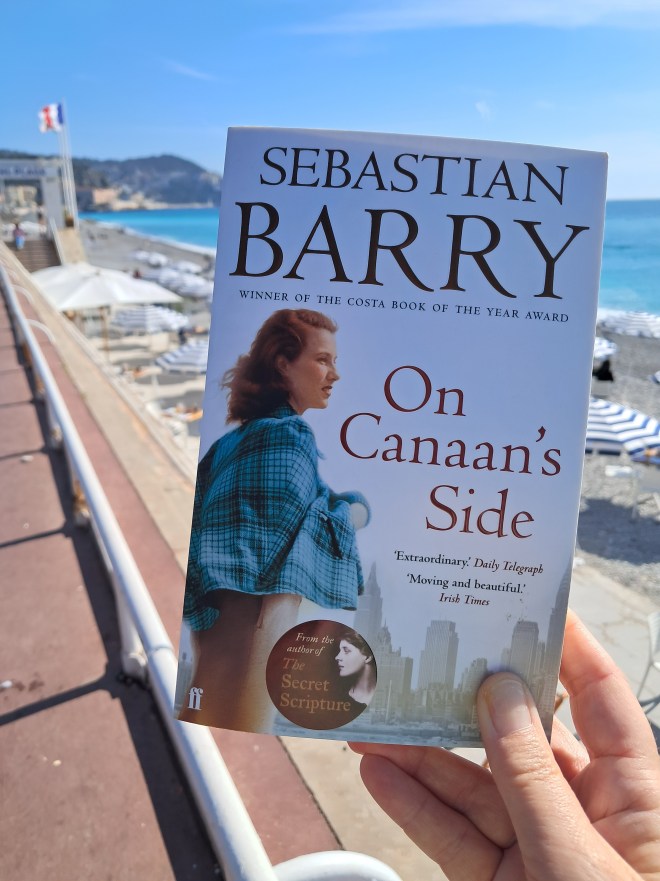

Continuing Reading Ireland Month 25 I finish the last of the three novels about the Dunne Family.

The final novel in the 4 book collection about the Dunne Family, first being the play about the Dad Thomas, the last superintendent of the Dublin Police, then his children Annie Dunne and Willie’s stories A Long Long Way and now Dolly, who we knew left Ireland for America as a young woman, but we never knew why.

Interestingly she too is based on a real ancestor, the Great Aunt of the author, whose true story only came out to him in recent years.

One Grievance Too Many

We meet her as Lily, a grieving octogenarian during the 2 weeks – each day a chapter – following the death of her grandson Bill, the boy she raised alone from 2 yrs of age, as she did her son.

I am so terrified by grief that there is solace in nothing. I carry in my skull a sort of molten sphere instead of a brain, and I am burning there, with horror, and misery.

So while in the present she is grieving and finding it difficult to find reason for still being alive, the novel is a form of her confession, an ode to herself, to all that has passed; so we are taken back to Dublin, to Wicklow, to what happened after the war, after the loss of Willie, to her meeting his young friend, the solider Tadg Bere and how their destinies become entwined.

A Fateful Meeting

‘The thing about Willie was,’ Tadg Bere was saying, ‘it wasn’t just you could be depending on him, you knew he was keeping a weather eye out for you, like you might a brother. So I was always thinking, that was a sorta compliment to his family, that they had reared him up in that frame of mind.’

Her father helps him find a job in the police force. Lily isn’t too sure about her feelings for him, their relationship has barely begun, when it reaches a significant turning point.

He was proud to be working, at something akin to soldiering, and something that would allow him to serve his country. He felt he was making a new beginning. He did not believe in any new Ireland, he devoutly loved the old one. The new force paid decently, but was otherwise poorly funded and put together in great haste. They barely had uniforms, and in the beginning wore bits and bobs of various forces, half army and half police, which is why they were dubbed the Black and Tans.

Ultimately the thing she desires, she can never truly embrace, as her life is lived always looking over her shoulder, always somewhat in fear.

Absence and Loss, Refuge in Cleveland

There are patterns in her life of men departing for war, her brother, her son, her grandson, and how it affected them all. And the departure of husbands, the losses she has borne, the perseverance, the continued service to others she has willingly offered, until the last revelation, the one that undoes her.

The title On Canaan’s Side is a reference to a bible story, to a song, about leaving a place of incertitude or danger to travel to a place of refuge. In the bible it is the “promised land”, in Irish history, it is to America they look as a place they ought to be safe and happy. It represents humbleness and receptivity, values that Lily has honoured, only to have encountered its curse, an inability to rise above her station.

Barry had this reference in mind too, after hearing it was mentioned by a newsreader in relation to the death of Martin Luther King, the tragedy of his killing, to be on Canaan’s side. There is a scene where King visits the house where Lily cooks, it seems out of place in the novel, but perhaps it is a nod to this reference.

Interestingly, Barry’s Canaan is Cleveland, Ohio, where Lily ends up; a place he developed an interest in due to the building of the Ohio Canal, a work of civil engineering designed to invigorate the northern territories up into Canada, already destroyed by the great flood in 1913.

The novel brilliantly portrays the struggle of making a new life, the lack of choices, the nostalgia of what has been left behind, the inability to prevent certain tragedies that arrive unbidden.

“I do believe writing for a writer is as natural as birdsong to a robin. I do believe you can ferry back a lost heart and soul in the small boat of a novel or a play. That plays and novels are a version of the afterlife, a more likely one maybe than that extravagant notion of heaven we were reared on. That true lives can nest in the actual syntax of language. Maybe this is daft, but it does the trick for me. I write because I can’t resist the sound of the engine of a book, the adventure of beginning, and the possible glimpses of new landscapes as one goes through. Not to mention the excitement of breaking a toe in the potholes.” Interview with Sebastian Barry, Words With Writers, 2011

Further Reading Listening

Talking About “On Canaan’s Side” with author Sebastian Barry, CBC Radio

Guardian review: On Canaan’s Side by Sebastian Barry – Sebastian Barry’s fifth novel is a lyrical evocation of trauma and exile, bearing a seemingly endless series of potent images

Author, Sebastian Barry

The 2018-21 Laureate for Irish Fiction, Barry had two consecutive novels shortlisted for the Booker Prize, A Long Long Way (2005) and the top ten bestseller The Secret Scripture (2008), before Old God’s Time was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2023. He has also won the Kerry Group Irish Fiction Prize, the Irish Book Awards Novel of the Year and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize.

His novels have twice won the Costa Book of the Year award, the Independent Booksellers Award and the Walter Scott Prize. Barry was born in Dublin in 1955, and now lives in County Wicklow.