Women in Translation Month

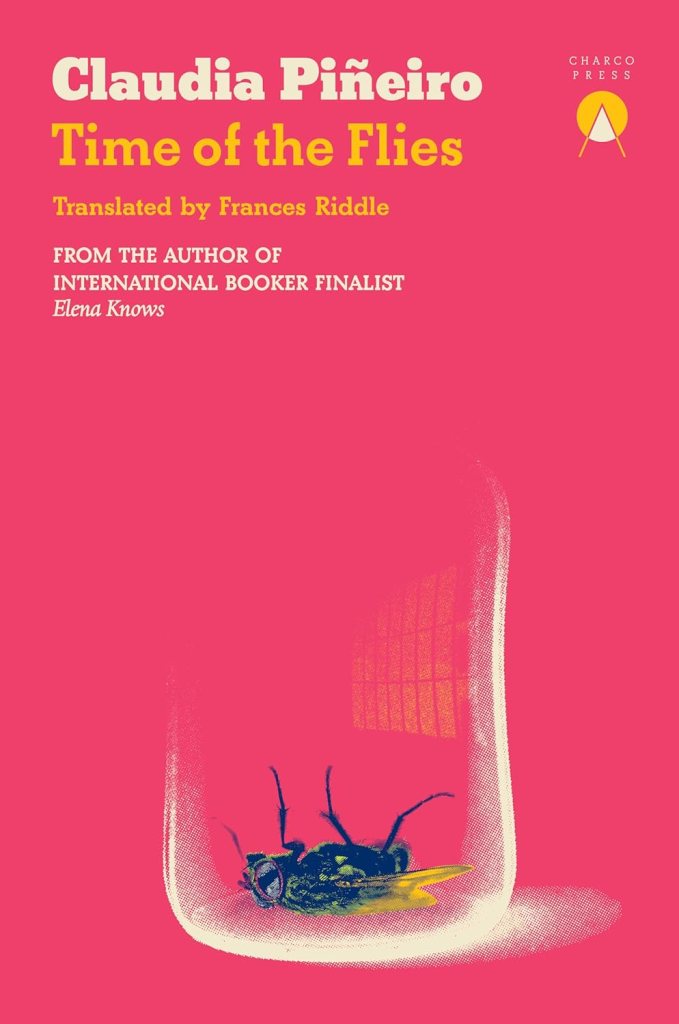

I read Claudia Piñeiro’s latest novel for #WITMonth. It is from the Charco Bundle 2024, a subscription where they send you nine titles, the best of contemporary Latin American fiction they are publishing throughout the year. It’s one of my absolute favourite things, an annual literary gift to me, surprise books that I haven’t chosen myself. And they are so good!

Also, it’s August. Women in Translation month. So I’m prioritising books in that category, another of my favourite things. World travel and storytelling through literature.

Claudia Piñeiro is fast becoming one of my favourite Latin American authors. This is her third book I have read. Elena Knows was Shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2022; it was intriguing, but the next one, A Little Luck was even better. More engaging emotionally, full of suspense, an immersive read.

Review

Time of the Flies has it all. The more I consider it, I find it is literary brilliance.

A past crime, a slow burning mystery, a complicated mother daughter relationship, a developing friendship between women who are used to not trusting anyone, unwanted motherhood, a dilemma that might be an opportunity or a trap. A sociological commentary on the lives, loves, wrath and resentments of women and thought provoking references to other works of literature, from classic mythology to contemporary feminism.

Female Friendships, Fumigations and Investigations

Inés, the mother of Laura ( a role she is trying now to deny) has been released from prison 15 years after killing her husband’s lover. She has set up a pest fumigation and private investigation business with fellow friend and ex inmate Manca.

FFF (flies, females and fumigations) a business run by women for women. Non-toxic pest control.

The two friends and business partners work separately but they consult each other when a case requires it, although Inés knows more about autopsies, fingerprints, and criminal profiles than Manca does about cockroaches.

A new client makes Inés an offer that might be an opportunity or a trap, she considers whether to pursue the opportunity and Manca, her friend and business partner investigates the client and becomes suspicious when she finds there is a connection between this woman and someone Inés knows.

She curses her fate and whatever recommendation or flyer that landed her at Susan Bonar’s house in the first place to be confronted by a part of her past that she does not deny but prefers to forget.

The Collective Voice, And Medea

Then there is a collective voice of feminist disharmony that enters the narrative every few chapters to opinionate on what just happened, if there is an issue that women might have an opinion on.

It’s never a consensus, it illustrates the difficulty of any collective voice that doesn’t resonate together, and demonstrates the aspects being considered on a topic. Other voices are quoted that challenge:

“There are many kinds of feminism in the world, many different political stances within the social movement and different critiques of our culture.” Marta Lamas Acoso. I don’t agree. Me neither. I do.

Each of these chapters begins with an epigram from Medea by Euripides (a Greek tragedy/play from 431 BC), that sets the tone for the theme that will be discussed. Like our protagonist Inés, Medea too, took vengeance against her philandering husband Jason, by murdering his new wife and worse, her own two sons.

This quote below precedes a discussion on the issue of one woman killing another woman, whether that is femicide. Equally interesting quotes from Rebecca Solnit and Toni Morrison are also referred to in the text.

Chorus:

‘Unhappy woman,

Feu, feu [Ah, ah] unhappy for your miseries.

Where will you turn? To what host for shelter?’

Once you realise what the collective voice is doing, it provides a pause in the narrative and allows other voices to engage with the reader. In case you missed that a significant issue had just appeared in the text you’re going to be confronted with it here. It doesn’t distract from the story (well, yes it does initially), however the chapters are only a couple of pages long. It adds depth to the narrative making this more of a literary novel, it pushes the reader to consider the issues, which some readers may not appreciate, but it is likely they will remember.

What About Those Flies

Inés sees a fly. In her eye. It comes and goes, it is a part of her. The doctor has checked it out and explained it away, but for her, it is significant. She understands the brain’s suppression mechanism that will make it disappear.

If she had to define it, she’d say it’s the feeling that there’s something fluttering around her head that she can’t catch, that there’s something right in front of her eyes that she can’t see. But it’s definitely not a fly.

Flies ascend in the narrative, they have a champion in Inés and we will even come across numerous literary references to them, some that hold them more in esteem than others. They are also that niggle that she feels, something that wants attention that she is not seeing.

Even Manca made a contribution to my literary education. IN her efforts to encourage me to write, she gave me a novel (I don’t read novels Manca); Like Flies from Afar, by one Kike Ferrari. Manca doesn’t read either, not even the instructions on how to use her appliances, but she went to the bookstore and asked for ‘one about flies’, and the bookseller said: ‘The fly as a methaphor, right? I’ll bring you one of the best crime novels of the year.’

(…)

(…)

The novel has its central mystery that is slowly unravelled, while it explores the complexity of the mother daughter relationship, the effect of abandonment and absence and the promise that a new generation can bring to old wounds.

(…)

(…)

(…)

So, Those Ellipsis’s

Though it was a slow read for me, it really got me in its grip and there was so much to consider beyond the mystery, like the collective voice, which makes the reader consider issues from different points of view.

Then there are the ellipsis’s. The pause, things left out, the reader’s imagination engaged, what are they? Pause for thought indeed. Usually present when there is dialogue, they make the reader consider why they are there. Are parts of the dialogue unimportant? Are they an invitation to imagine what was said in between? Whatever the intention of the author, the effect is to awaken the reader to their presence and make you think about the why.

By the time I finished this, I absolutely loved it, for everything. For its central storytelling, its reflective invitation, the literary references, the collective voice and its ability to keep me entertained and interested and intrigued. A quirky, enticing, novel that praises flies and finds all these intriguing literary references to them. It is a cornucopia of elements amidst great storytelling.

Further Reading

Read an Extract of Time of the Flies by Claudia Piñeiro

Actualidad Literatura: The Time of the Flies <<El tiempo de las moscas>> reviewed by Juan Ortiz

Author, Claudia Piñeiro

Born in Burzaco, Buenos Aires in 1960, Claudia Piñeiro is a best-selling author, known internationally for her crime novels.

She has won numerous national and international prizes, including the Pepe Carvalho Prize, the LiBeraturpreis for Elena Knows and the prestigious Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize for Las grietas de Jara (A Crack in the Wall). Many of her novels have been adapted for the big screen, including Elena Knows (Netflix).

Piñeiro is the third most translated Argentinean author after Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortázar. She’s also a playwright and scriptwriter (including popular Netflix series The Kingdom). Her novel Elena Knows was shortlisted for the 2022 International Booker Prize.