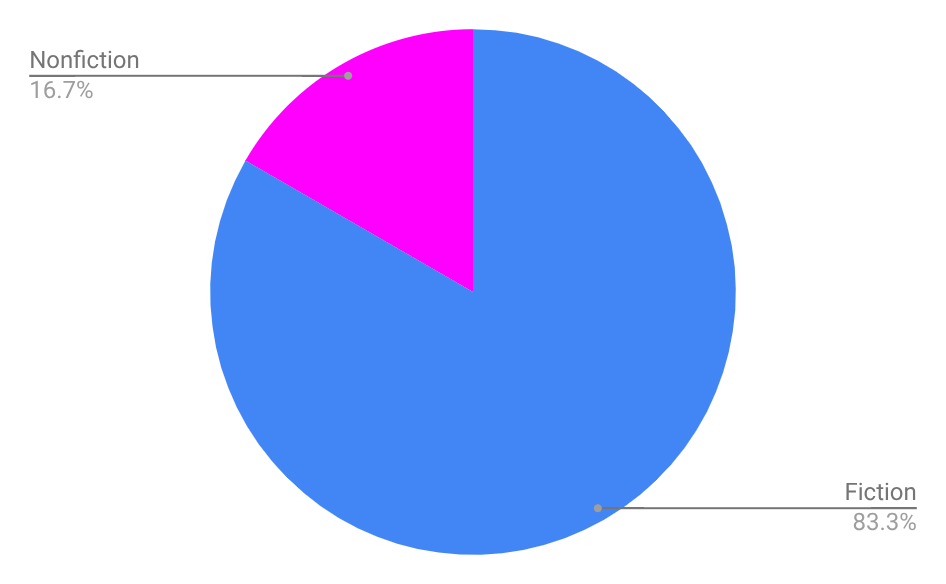

In 2025, I read 75 books from 22 countries (the exact same number of countries as in 2024), 55 of those titles were fiction and 20 were nonfiction.

73 percent of my reads were by female authors and 27% by male authors. Of the total books read, 15% were books in translation, originally written in a language other then English.

I will be sharing my One Outstanding Read of the year, the runner up, Top 9 Fiction, tomorrow my Top 8 Non-Fiction and since there were so many excellent reads, the following day Top 7 Reads in Translation.

One Outstanding Read of 2025

My One Outstanding Read of the year for 2025 is the non-fiction memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me (2025) by Arundhati Roy, (review to come), a phenomenal, engaging, wide-ranging book that is as much about her mother Mary Roy as it is herself. From the back cover:

‘In these pages, my mother, my gangster, shall live. She was my shelter and my storm.’

It is about the family she was born into, the matriarch Mary Roy she was raised by, the controversy around their housing, as her mother struggled initially to raise two children on her own, the lawsuit Mary Roy would launch against her brother and mother that changed inheritance laws in their state; the school Mary Roy founded and how it was being the child of the school principal. We follow Arundhati Roy through her seven year estrangement from family, her architectural studies, her early film-making ventures, her relationships and difficulties in them due to the strong values she held.

“When it came to me, Mrs Roy taught me how to think, then raged against my thoughts. She taught me to be free and raged against my freedom. She taught me to write and resented the author I became”

It is a raw, honest account and an insight into a passionate, dedicated, creative individual, who won the Booker Prize with her debut novel, The God of Small Things (1997) a feat that had a major effect and influence on what she has been able to do in life, and enabled the support she has been able to provide to other causes, in order that they remain independent and are not compromised by the stultifying agendas of large corporate and NGO organisations.

Outstanding Read Runner Up 2025

Somebody is Walking On Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys (2025) by Mariana Enriquez (Argentina) tr. Megan McDowell (Spanish) – I have to mention this book as it was also an outstanding, unique and far-reaching book that kept me entranced for the most part of October, as the author travels in 13 countries visiting 21 cemeteries, (something she is passionate about) sharing cultural anecdotes about each country, history, legend and their relationship to the dead. She wrote these essays over a period of about 25 years, starting with a visit to Genoa, Italy with her mother through two and half decades of experience, learning, and journeying that no doubt continues in her life today.

It’s not so much macabre, as it is insightful to learn about some of the communities of people she comes across, like the Welsh speaking community in Patagonia, what it means to have Taphophilia syndrome, the controversy surrounding the Pietro Gualdi marble sculpture of a seated woman in New Orleans, people who have already constructed elaborate tombs for themselves ahead of time, the dilemma of the 12th century Holy Innocents Cemetery in Paris that led to the catacombs, the first date she has with her Australian boyfriend, taking him to the aristocratic Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires, where Eva Peron was finally laid to rest (after much debate, body snatching and travel). The entire book was an eye-opener and an unforgettable read and one I highly recommend.

Top Fiction

Small Worlds (2023) by Caleb Azumah Nelson (UK/Ghanaian) – a brilliant, meandering coming-of-age story set mostly in Peckham, London. A story-line that spans three years as he finishes school and decides what to do next, it is an introspective excavation of a young British-Ghanaian man’s soul, the situations he will encounter and confront, as he matures and grows into a version of himself that he likes. I read this early in the year and this one is my Number 1. Top Fiction of the Year.

Second Class Citizen (1974) by Buchi Emecheta (Nigeria/UK) – I read The Joys of Motherhood by Buchi Emecheta some years ago and loved it and have long wanted to read this. It’s absolutely brilliant and poignant and tells the story of a young Nigerian girl in the 1960’s, much like the author herself, determined to get herself an education and raise herself up in the world, which she does – until a marriage and in-laws start to rely on her as their income source, so she sets London in her sights, only for the challenges to increase as children begin to appear – as a woman she has no control over her reproductive rights. It is a powerful story of a woman dealing with and overcoming the odds, in her home country and as an immigrant.

Buchi Emecheta, while raising five children, published novels, obtained a degree in sociology, wrote plays for television and radio, worked as a librarian, teacher, youth worker and sociologist, and community worker. She was one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists in 1983.

Black Woods, Blue Sky (2025) by Eowyn Ivey (Alaska) – Eowyn Ivey remains one of my favourite authors, most known for her debut novel The Snow Child (2012). She also wrote The Bright Edge of the World (2016) and now her latest, a novel that subtly references Beauty and the Beast, is her most autobiographical novel and again set in her local region of the wilds of Alaska.

It is the story of a troubled, young mother Birdie, her six year old daughter Emaleen and a reclusive character Arthur. Ignoring the warnings of those who care about them, Birdie and Emaleen move to Arthur’s isolated cabin in the mountains on the far side of the Wolverine River, far from roads, telephones, electricity, and outside contact. At first everything is idyllic, until it is not and this sense of things not being quite right creates acute suspense while reading. Ivey has a wonderful way of capturing the magic and menace of the wilderness while creating down to earth characters and that hint of an unsettling feeling lurking beneath the narrative.

Fundamentally (2025) by Nussaibah Younis (UK/Iraq/Pakistan) – Not reviewed here, but one of my favourite reads of 2025, I just loved the comic narrative voice of Fundamentally and the unique setting of a UN workplace in Iraq, even if some of the characters were somewhat cliche. Shortlisted for the Women’s Prize 2025.

When academic Nadia is disowned by her puritanical mother and dumped by her lover, she decides to leave, accepting a UN job in Iraq. Tasked with rehabilitating ISIS women, Nadia observes the inside of world international aid and finds herself quickly compromised. As the tension ratchets up, as Nadia tries to make up for her mistakes, the humour fades and the danger increases, as they cross lines that can’t be reversed.

Younis is a fearless, talented writer, creating fiction from a place of knowledge that not too many authors occupy and is able to bring depth, humour and insight to serious subjects. I found it a relief to read a light version of the harsh reality of war zones and displacement, still having the imprint of Sally Hayden’s ambitious award-winning work of nonfiction, My Fourth Time We Drowned, which depicts the plight of those seeking asylum, risking their lives taking small craft across the Mediterranean.

The Marriage Portrait (2022) by Maggie O’Farrell (Ireland/UK) – In 1540 -1561 Renaissance Italy, we encounter the story of Lucrezia of Florence, who, due to the death of her older sister Maria, becomes the intended fiance of the man her sister was going to marry, Alfonso of Ferrara. It tells of her childhood in Florence, her year of wretched wifedom, her solace in creating art and the act of sitting for a portrait that she dislikes.

Told in twin timelines, childhood and marriage, beginning with a historical note in the opening pages about her alleged death, there is an underlying tension and suspicion all the way through the narrative which adds to the pace and intrigue. The character of Lucrezia is exquisitely constructed and rich in visual imagery, thanks to her artistic inclinations, despite the fact that she is often confined to quarters. The era of Renaissance Italy, the day to day lives, the close environment of these dynastic families is intricately portrayed and sumptuously imagined.

Look out for more historical fiction from Maggie O’Farrell in 2026, Land is set in 1865 Ireland.

Clear (2024) by Carys Davies (Wales/UK) – Clear is a short historical novella that gripped me from the opening pages and transported me to 1843 Scotland, the time of the Great Disruption, the Highland Clearances. It is about a quiet, worrisome, rebel pastor, John Ferguson, his wife Mary and Ivar, a lone islander out in the North Sea, somewhere between the Shetland Islands and the coast of Norway.

John, like other rebel ministers who signed the controversial Act of Separation and Deed of Demission, is under financial pressure to meet his new responsibilities and accepts a paid role from a landowner’s factor against his wife’s wishes. He must visit a remote island in the north and evict the last inhabitant. Evocative of its time and place. I thought this was a brilliant, atmospheric tale.

Flashlight (2025) by Susan Choi (US) – Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2025, Flashlight interested me because of its portrayal of a cross-cultural marriage (American and Korean-Japanese) and family that highlights the tensions between adults with different backgrounds and expectations, coping within one culture (America), while Louisa, the child of that union navigates her own life and connection to her parents.

Also the further stretch of scope and understanding it provides, as the narrative moves from the US to Japan to North Korea, because it concerns a family exiled from Jeju Island in South Korea, living in Japan, wanting to return. Their son Serk (Louisa’s father) has grown up and been educated in Japan and values that education, resists his family’s desire, while they wish to take up an offer to return.

When Serk goes missing, the narrative splits and we follow each family member on their own timeline, observing our characters while learning something of a complicated history of Korea and Japan. While slow to begin, this became captivating, mysterious and frightening as time began to run out for a man trying to return and a daughter trying to find herself. I loved the immersion in another culture, the multiple cultural perspectives and coming to understand the complication of borders, ethnicities, allegiances, and the creepy stealth of some nations and complete (or deliberate) ignorance of others.

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny (2025) by Kiran Desai (India) – I do love a good cross-cultural novel, and one that is in part set in India, by a known author, sounded promising. As soon as I saw the Booker longlist I knew I would be reading this, and I loved it. The story is about two young people who have just finished studying in the US, Sunny is working as a freelance journalist and Sonia is in a college library, looking for an internship. Their families have a connection but are no longer close, however a letter arrives suggesting marriage, to absolve a past discretion, but goes nowhere.

It is an interesting navigation of their young adult lives, where they struggle to cope with the freedom and direction their lives might take, now that they are living outside of their country and culture. Both must deal with challenging issues on their own, their families far away and ignorant of their dilemmas. On a trip home, the two cross paths, make a strong connection, only to diverge again. This is enough to ignite in the reader, a wish that they might meet again, though it is clear the timing had not been right.

I loved this immersive, meandering novel, the loneliness and confusion of the protagonists, the clash of cultures and past/present values, the defiance and stubbornness of each parent, the multi-generational threads as everyone is going through their transition and it’s a wild, contemporary ride to the end. Brilliant.

The Correspondent by Virginia Evans (US) – Nothing like a feel good novel to wrap up the end of the year. This is a charming book of letters by a dedicated 73 year old retired law clerk and correspondent who sits at her desk every morning to write letters, emails, notes, through which we come to learn all the issues she’s currently juggling and something of her stubborn, somewhat dogmatic attitude. It’s also an unlikely word-of-mouth book that is enjoying some success thanks to readers, not marketing hype.

It’s entertaining, has multiple engaging storylines and some of the letters contain excellent book recommendations, which is always fun for readers. There’s mystery, loss, relationship troubles, mother-daughter issues, potential love interest(s) and a tribute to the lost art of letter-writing. Loved it!

* * * * *

So that’s my Top 9 Fiction Reads for 2025, tomorrow I’ll share my Top 8 Non-Fiction Reads for 2025 and after that I’ll share my Top 7 Translated Reads of 2025.

Are any of these in your Top Reads of 2025? Let us know in the comments your thoughts, or share your favourite fiction read of 2025, I would love to know.