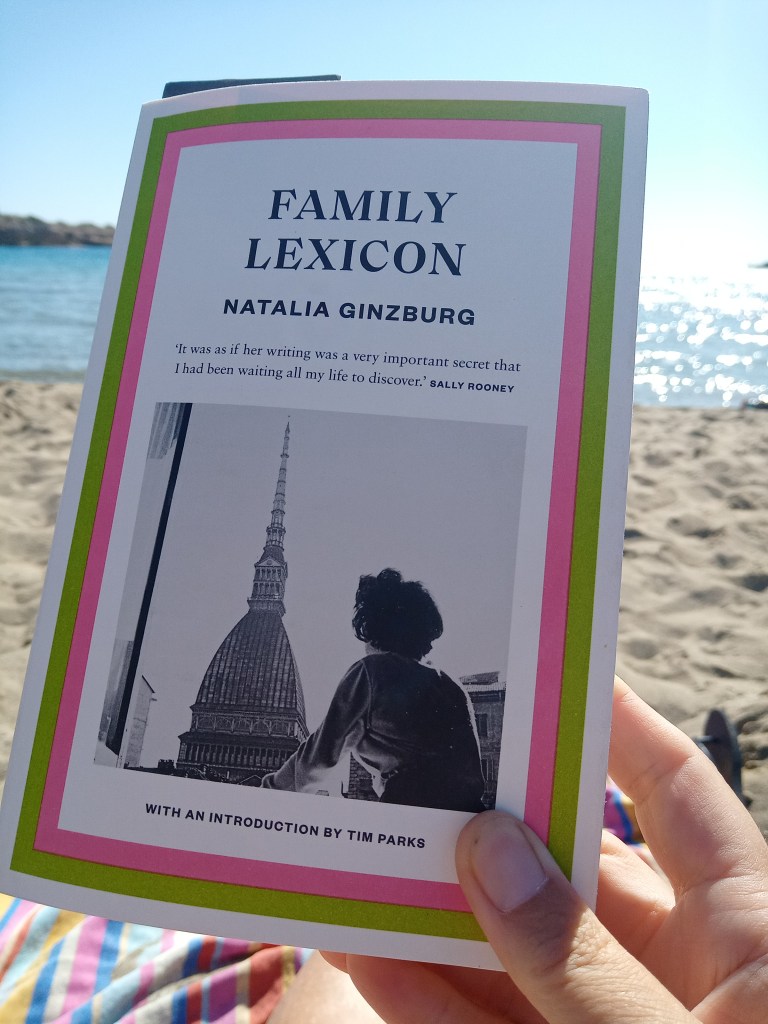

Family Lexicon (Lessico Famigliare) is a unique memoir or work of autofiction of family life and by Italian author Natalia Ginzburg. She advises the reader to read it like a novel, the places, events and people are real, recalled in the way she knew them, most often by the way they used language.

This is the first of her books I have read and since life informs fiction, I thought I would meet the characters from her life before reading more of her novels.

Family Sayings & Life Lessons

Rather than speak of her life as a narrative from childhood onwards, of her own exploits, she focuses on the characters around her, building a picture of them through noting their tendencies and favoured expressions. The things they said most often, which creates impressions of attitudes and the force of personality, so that we come to know something of the household, from when they were all together, through the war and beyond.

I had little desire to talk about myself. This is in fact not my story but rather, even with gaps and lacunae, the story of my family.

The character that looms largest in the family is her father, the patriarch. Devoid of sentiment, Ginzburg familiarises us with his brusque ways, his favourite insults, criticisms, judgments and orders. Taking the family on holiday to the mountains was a form of boot camp, compulsory hiking from dawn to dusk. His own mother, though joining them, refused to stay with him, preferring a less regimental nearby hotel. The children complaining of boredom elicited:

‘You lot get bored’, my father said, ‘because you don’t have inner lives.’

There were five children in the family, Natalia being the youngest, the quiet observer, the astute note-taker.

Though they live in different cities, countries and rarely see each other, it is the family lexicon that unifies them, that one word or phrase that causes them to fall back into old roles and relationships, into childhood and youth again.

Those phrases are our Latin, the dictionary of our past, they’re like Egyptian or Assyro-Babylonian hieroglyphics, evidence of a vital core that has ceased to exist but that lives on in its texts, saved from the fury of the waters, the corrosion of time. Those phrases are the basis of our family unity and will persist as long as we are in the world, re-created and revived in disparate places on the earth, whenever one of us says, ‘Most eminent Signor Lipmann’, and we immediately hear my father’s impatient voice ringing in our ears; ‘Enough of that story! I’ve heard it far too many times already!’

On her mother, who is the opposite to the father:

But my mother’s affections were as erratic as ever, her relationships inconstant. Either she saw someone every day or she never wanted to see them. She was incapable of cultivating acquaintances just to be polite. She always had a crazy fear of becoming ‘bored’, and she was afraid visitors would come to see her just as she was going out.

Her mother preferred the much younger company of new mothers then those her own age who she referred to as “old biddies”.

Notables or Nobodies, An Extended Family

While much of what she recalls is far from endearing, it resonates loudly as realistic, the phrases that stand and repeat through time, by their nature, they are those that mark in the memory, while others float away like debris.

New characters arrive unbidden and I find myself reading back a few pages to see if they have been mentioned before, knowing their significance, like Leone Ginzburg, the man who will become her husband. He enters the text with his friend Pavese and the publisher they worked for; Pavese wrote poetry, as many we meet on these pages do, while Leone’s true passion was politics, at one time jailed and perceived as a dangerous conspirator.

As time passes and Natalia moves from Turin, to the countryside during the war and eventually to Rome, different people are around or mentioned, connected to the family in some way and again. We see snapshots of them, as she observes or listens to them during a significant event, though never how she feels, it is as if her memory exists only in the face and words of those who witness.

Words: Weapons or Wisdom

When Leone is arrested and doesn’t return home, she is at a loss what to do.

Leone was arrested in a clandestine printer’s shop. We were living in an apartment neat the Piazza Bologna and I was home alone with my children. I waited, and as the hours went by and he failed to come home, I slowly realised that he must have been arrested. The day passed and then the night, and the next morning Adriano came over and told me to leave the lace immediately, because Leone had, in fact, been arrested and the police might show up at any moment.

When she recalls this terrifying moment, the imprint of her memory is all about Adriano, the relief in seeing him a balm to the more terrifying thoughts she must have had for herself and her children.

For the rest of my life, I will never forget the immense solace I took in seeing Adriano’s very familiar figure, one I’d known since childhood, appear before me that morning after so many hours of being alone and afraid, hours in which I thought about my parents far away in the north and wondered if I would ever see them again. I will always remember Adriano hunched over as he went from room to room, leaning down to pick up clothes and the children’s shoes, his movements full of kindness, compassion, humility and patience. And when we fled from that place, he wore on his face the expression that he’d had when he came to our apartment for Turati; it was that breathless, terrified, excited expression he wore whenever he was helping someone.

Poetry as Freedom

During fascism, novelists and poets were silenced, starved of words, forbidden to freely express themselves, having to choose carefully from a slim, censored collection. In the post-war period, there was initial exuberance, followed by a reckoning, as the language of poetry and politics mixed, then separated. Perhaps it is was this experience, as much as being the youngest child, often interrupted, that contributed to her writing style.

At the time there were two ways to write: one was a simple listing of facts outlining a dreary, foul, base reality seen through a lens that peered out over a bleak and mortified landscape; the other was a mixing of facts with violence and a delirium of tears, sobs and sighs…It was necessary if one was a writer, to go back and find your true calling that had been forgotten in the general intoxication. What had followed was like a hangover, nausea, lethargy, tedium. In one way or another, everyone felt deceived and betrayed, both those who lived in reality and those who possessed or thought they possessed a means of describing it. And so everyone went their own way again, alone and dissatisfied.

Tim Parks tells us in the introduction that many of the characters and names mentioned are well-known figures in Italian history, however Ginzburg writes of them all with egality, they are friends and family, ordinary humans, with quirks and foibles, whether they are written about elsewhere under their various labels or not, here they are written about purely in relation to their connection to her family. In the end pages however, there are notes on all the names, foreign language phrases, excerpts that expand on the references casually made in the text.

page 241 my mother said, “Many clothes, much honour!” : a parody of the facist slogan “Many Foes, Much Honour”.

While initially the style feels quite abrupt, direct and unflinching, over time it becomes like a jigsaw puzzle, the family and their friends, acquaintances and situation slowly emerge with greater clarity, depicting something greater than a mere memoir of one member, it becomes an historical document in itself, recording the voices, concerns and passions of a group of people that together gave Natalia Ginzburg a lifetime of writing inspiration.

Much is made elsewhere of this period in the 1930’s and 1940’s Italy being a hotbed of anti-Facist activity and this family being in the midst of it. Many of their friends were noted publishers, writers, professors, scientist -known to be anti-Fascist and Jewish.

I enjoyed the book all the more for not being aware of the labels and infamy of the characters while reading it, but it adds another layer of interest to read the end notes which give potted bio’s of those characters and further explanations to some of the phrases used or events written about.

Highly Recommended and I’m looking forward to reading her book of essays The Little Virtues and her debut novel The Dry Heart and more, coming soon!

Further Reading

New Yorker: Rediscovering Natalia Ginzburg by Joan Acocella, July 22, 2019 – In Ginzburg’s time, Italian literature was still largely a men’s club. So she wanted to write like a man.

The guardian: If Ferrante is friend, Ginzburg is a mentor by Lara Feilgel, 25 Feb, 2019 – the complex world of Natalia Ginzburg.

Natalia Ginzburg, Author

Natalia Ginzburg (1916-1991) was born in Palermo, Sicily. She wrote dozens of essays, plays, short stories and novels, including Voices in the Evening, All Our Yesterdays and Family Lexicon, for which she was awarded the prestigious Strega Prize in 1963.

She was the first to translate Marcel Proust’s Du côté de chez Swann into Italian.

Her work explored family relationships, politics and philosophy during and after the Fascist years, World War II. Modest and intensely reserved, Ginzburg never shied away from the traumas of history, whether writing about the Turin of her childhood, the Abruzzi countryside or contemporary Rome—approaching those traumas indirectly, through the mundane details and catastrophes of personal life.

She was involved in political activism throughout her life and served in the Italian parliament between 1983 to 1987. Animated by a profound sense of justice, she engaged with passion in various humanitarian issues, such as the lowering of the price of bread, support for Palestinian children, legal assistance for rape victims and reform of adoption laws.

She died in Rome in 1991 at the age of seventy-five.

I’ve got two titles by Ginzburg so I’m going to bookmark this and hope I remember it when I come to read them!

(Maybe #NovellasInNovember, eh?)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes, she wrote plenty of novellas, this work is probably one of her more lengthy volumes. I didn’t get to any WIT in August, so I’m making up for it now, feeling somewhat deprived when I have so many great books waiting to be read. It was a busy summer, very happy for the arrival of autumn.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This looks a worthwhile read, especially as I have become interested in this period of Italian history. I’ll look out for it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sure like me, you’ve been coming across a few of her books being reviewed on the pages of bloggers we follow, I’ve been warming up to a reading season of Natalya Ginzburg for a while and loved this first one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right. I’ll have to get a few lined up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely review, Claire, and I’m so glad you’ve found your way into Ginzburg’s work. She really is a terrific writer with an excellent ear for dialogue, and I think that comes over in your review. Family Lexicon will probably be my next by her. In fact, I’ve been trying to save it for a while as it’s considered to be one of her best!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Jacqui, it’s thanks to your continual sampling of her works and reviews that I eventually decided to get 6 of her collection. I was tempted by the idea of reading an overview of her life and meeting the characters considered important or influential and so I’m all the more excited to read her fiction and essays having done that.

Family Lexicon is such a unique work, I love how it felt a little mystifying to begin with as I adapted to her style, then there is a moment where you’re in it, it’s been normalised and the picture in the canvas, so to speak, appears. I look forward to reading your thoughts on it and thank you for bringing her work to my attention.

LikeLike

A pleasure. I’m all the more eager to get to it now that I’ve read your review!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My introduction to Natalia Ginzburg’s work was ‘The Little Virtues,’ recommended to me by an Italian acquaintance, particularly for an essay in it, “Worn Out Shoes.” The collection is a gem, and I subsequently read some of Ginzburg’s novels as well as “Family Lexicon,” which I appreciated on so many levels, especially after reading the Joan Acocella essay you mention.

LikeLike

Thank you Deborah, I remember that you have mentioned and recommended Natalia Ginzburg to me in the past as well, thank you too for bringing her work to my attention, truly a gifted writer. I have those essays and already have dipped into a couple, savouring them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Dry Heart by Natalia Ginzburg tr. Frances Frenaye – Word by Word

Pingback: Top Reads of 2023 – Part 2 – Word by Word

Pingback: Valentino (1957) by Natalia Ginzburg tr. Avril Bardoni (Italian), Intro by Alexander Chee – Word by Word

Pingback: Sagittarius by Natalia Ginzburg (1957) tr. Avril Bardoni – Word by Word

Pingback: Her Side of the Story by Alba de Céspedes tr. Jill Foulston – Word by Word

Pingback: The Little Virtues by Natalia Ginzburg tr. Dick Davis – Word by Word

Pingback: Best Books of 2025 Top Reads in Translation – Word by Word