Today the Booker Prize Judges shared their shortlist of six novels, narrowed down from the 13 novels in the longlist from an original list of 156 novels.

The panel is chaired this year by artist and author Edmund de Waal, joined by award-winning novelist Sara Collins; Fiction Editor of the Guardian, Justine Jordan; world-renowned writer and professor Yiyun Li; and musician, composer and producer Nitin Sawhney.

The Shortlist of Six books below includes five women and authors from five countries including the first Dutch author to be shortlisted, the first Australian in 10 years. Below the description is a brief comment from the judges and the reason they think reader’s will love that book:

The Safekeep by Yael van der Wouden (Netherlands) – An exhilarating tale of twisted desire, histories and homes – and the legacy of one of the 20th century’s greatest tragedies.

Set in the Netherlands after the war, a quietly devastating novel of obsession and secrets, in which a relationship between two women in a perfectly ordered Dutch household becomes a story of the Holocaust.

We loved how atmospheric this book is. The austerity of these years is powerfully evoked, the particularity of where each teaspoon and coffee cup belongs is beautifully calibrated. But we adored the dynamic of the relationship between Isabel and Eva, the way they inhabit this charged space, always aware of each other and their bodies.

Orbital by Samantha Harvey (UK) – Six astronauts rotate in the International Space Station. They are there to do vital work, but slowly they begin to wonder: what is life without Earth? What is Earth without humanity?

This brief yet miraculously expansive novel, set aboard the International Space Station is inflused with such awe and reverence that it reads like an act of worship.

This novel is superbly crafted and lyrically stunning. Sentence after sentence is charged with the kind of revelatory excitement that in a lesser book would be eked out of plot alone.

Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner (US) – A woman is caught in the crossfire between the past and the future in this part-spy novel, part-profound treatise on human history.

A thought-provoking novel of ideas, wrapped up in a page-turning spy thriller. Kushner’s prose is juicy, her narrator jaunty, her world-building lush.

Novels that investigate what it is to be human can veer into the sentimental; this one is utterly flinty and hard-nosed. And yet, there’s mystery at its core – both the mystery of human origins and of individual identity. ‘What is it people encounter in their stark and solitary 4am self? What is inside them?’ As with the caves that play such a key part in the book, Kushner taps into something profound.

Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood (Australia) – The past comes knocking in this fearless exploration of forgiveness, grief and female friendship.

Set in a claustrophobic religious retreat in rural Australia, this is a fierce and philosophical interrogation of history, memory, nature and human existence.

Contemporary issues – climate change and a global pandemic – can sometimes appear as flat concepts or stale ideas in fiction, but Stone Yard Devotional is able to make both topics locally and vividly felt as haunting human stories.

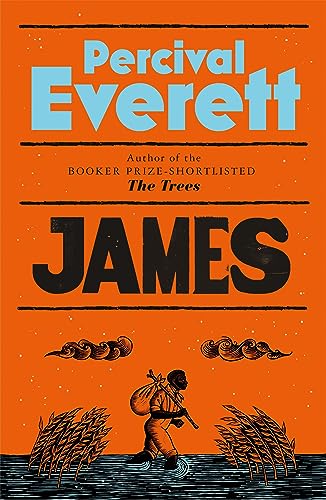

James by Percival Everett (US) – A profound meditation on identity, belonging and the sacrifices we make to protect the ones we love, which reimagines The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

A powerful, genre-defying, revisionist exploration of slavery, the indomitable resilience of the human spirit and the pursuit of freedom. It subverts all expectations.

While the book deals with the horrors of slavery, it also examines universal themes of identity, freedom and justice. Everett challenges us to question, and reflect on, the nature of morality, the corrupting influence of power and the indomitable resilience of the human spirit.

Held by Anne Michaels (Canada) – In a narrative that spans four generations from 1917, moments of connection and consequence ignite and re-ignite as the century unfolds.

A lyrical kaleidoscope of a novel created from the scattered images and memories of four generations of a family. Few books could sustain a pitch of poetic intensity.

We loved the quietness of this book: we surrendered to it. The large themes are of the instability of the past and memory, but it works on a cellular level due to the astonishing beauty of the details. Whether it is the mistakes that are knitted into a sweater so that a drowned sailor can be identified, or the rituals of making homecoming pancakes, or what it feels like to be scrutinised as you are painted, the novel makes us pause.

The Verdict

So I’m surprised and disappointed not to see My Friends by Hisham Matar on the list, I thought it was excellent; it is great to see Percival Everett’s masterpiece James there, I loved it. I have read Orbital and it was okay, though I felt quite detached from it and the characters, while reading.

Of the others, I’m curious enough to read an extract from Stoneyard Devotional, and Held, though the Anne Michaels might be a bit much for me if its anything like her much earlier Fugitive Pieces. I’m not sure about Creation Lake, it’s giving me Birnam Wood, Eleanor Catton vibes, so likely not for me. And now I have these two previous Booker Prize winning novels to read, thanks to a lucky book haul at the Vide Grenier in Ansouis Village yesterday.

So what do you think of the shortlist? Any recommendations? Disappointments?

Read An Extract

If you want to check out some of the first chapter of any of these books, you can read an extract here.

The Booker Winner

The announcement of the winner of the Booker Prize 2024 will take place at a ceremony and dinner held at Old Billingsgate in London on Tuesday, 12 November.