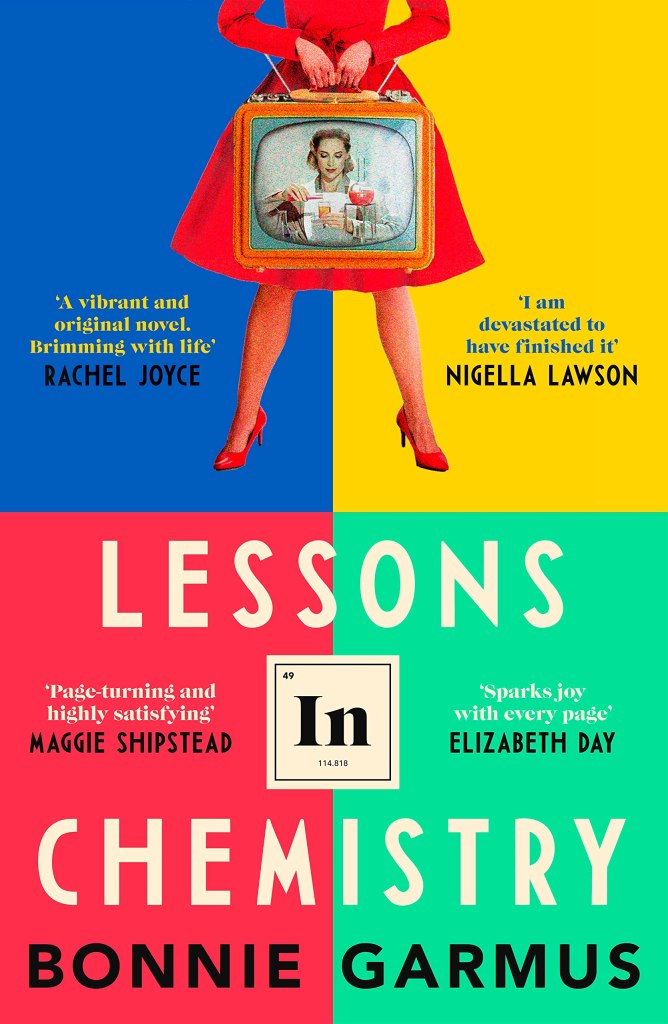

I admit that I likely wouldn’t have read this if it hadn’t been pressed on to me to read by 3 people. I’ve seen it rise up the reading charts, and in reading it, I recognise that quality that makes some books become the one that goes beyond avid and even occasional readers, to reach those that rarely if ever read at all. And boom, it’s a worldwide bestseller.

Lessons in Chemistry centres around a young woman scientist/chemist Elizabeth Zott. It’s set in America between 1952 and the early 1960’s and Elizabeth has forged a path into science, and in the opinion of some has gone too far down that path. Her academic career is eventually upended by one man who decides to take matters in his own hands to stop her, though with her Masters complete, she is still able to find work in a lab.

Despite continued setbacks, prejudices, sexism, attempts to discredit or steal her work, she perseveres with her research. One day she meets her equally young, revered, male colleague Calvin Evans, helping herself to his stocks of beakers and it signals the beginning of a meeting of minds, a chemistry, between the two, that changes their lives.

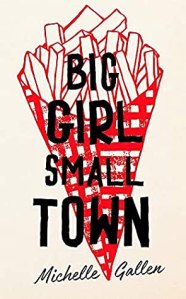

Elizabeth is one of those quirky characters, like Eleanor in Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine and Majella in Michelle Gallen’s Big Girl, Small Town, she lacks a filter, is not overly sensitive to bad behaviour, innuendo and discrimination – rather she responds to it neutrally, factually, in a straight up, unemotional manner.

As we read, we realise how unusual that is, because every woman of a certain age, will recognise these workplace dynamics and recall themselves or someone in this situation and will remember how it was – and the pressure to dismiss it, to sweep it under the carpet, to not challenge it – because of the consequences (and lack of).

Elizabeth too receives the consequences of the relentless, ever-present misogyny, she gets kicked out out university, she’ll get fired, however she continues to bounce back, challenging the status quo.

She perseveres, because she is logical, because she had a different upbringing and wasn’t groomed and conditioned in the way many girls were to accept what she was encountering. It’s not because she has an attitude, it’s because of who she is, at her core. It is humorous because she perseveres, because she takes charge and continues to make her own decisions, never becoming the victim. She is never silenced.

Some describe this as funny. In my opinion, it is not. It is very real – but it is highly unusual to encounter a person, even in fiction, who exposes these aspects of society, and rises – and then finds a way – as she does with her new role, presenting cooking lessons on midday television as science lessons to housewives – starting a mini revolution.

“That’s why I wanted to use ‘Supper st Six’ to teach chemistry. Because when women understand chemistry, they begin to understand how things work.”

Roth looked confused.

“I’m referring to atoms and molecules , Roth, she explained. “The real rules that govern the physical world. When women understand these basic concepts, they can begin to see the false limits you create for them.”

“You mean by men?”

“I mean by artificial cultural and religious policies that put men in the highly unnatural role of single-sex leadership. Even a basic understanding of chemistry reveals the danger of such a lopsided approach.”

I won’t share the quote, because reading it for the first time is too good in the context of the story, but when the rowing coach complains to Elizabeth about how his wife has been influenced by her show, was one of my favourite laugh out loud moments in the book.

Elizabeth slowly gathers around her a supportive, small inner circle of people (and a dog) who get her, the relief of having such people in her life is palpable to the reader. Her friend Walter Pine, articulates in a moment, when he recalls the effect of first meeting her, a day she came to challenge him over his daughter stealing her daughter’s lunches.

She’d stormed past his secretaries in her white lab coat, hair pulled back, voice clear. He remembered feeling stunned by her. Yes, she was attractive, but it was only now that he realised it had little to do with how she looked. No, it was her confidence, the certainty of who she was. She sowed it like a seed until it took root in others.

The writing is pitch perfect, the story hums along at pace and like all greats summer reads, it gives the reader a sense of satisfaction. I would call this ‘magical satire’, because there is a wonderful dog character named Six-Thirty, whom Elizabeth assumes is intelligent, so teaches him a vast vocabulary, although she gives him what might be construed as superpowers, but he is a great character, going through his own coming-of-age, as he leaves an abusive environment to join their quirky family community.

Ultimately, perhaps it is merely about how in all aspects of life,even those deemed more masculine, women bring something different, something complementary and when we can work in partnership, alongside others, the result can be to empower and uplift and improve everyone’s lives, not just those in power, who want to dominate, or those beneath them who continue to support that model.

Perfect relaxing, holiday reading, highly recommended.

Bonnie Garmus, Author

Bonnie Garmus is a copywriter and creative director who has worked widely in the fields of technology, medicine, and education. She is an open-water swimmer, a rower, and mother to two daughters. Born in California and most recently from Seattle, she currently lives in London with her husband and her dog, 99.

Lessons in Chemistry is her debut novel, it was nominated by many bookstores as their Book of The Year and was the Goodreads Best Debut of 2022.

Big Girl, Small Town takes place during a week in the life of socially awkward but inwardly clear-eyed 27-year-old Majella who from the opening page we learn has a list of stuff in her head she isn’t keen on, a top ten that hasn’t changed in seven years. Things like gossip, physical contact, noise, bright lights, scented stuff, sweating, jokes and make-up.

Big Girl, Small Town takes place during a week in the life of socially awkward but inwardly clear-eyed 27-year-old Majella who from the opening page we learn has a list of stuff in her head she isn’t keen on, a top ten that hasn’t changed in seven years. Things like gossip, physical contact, noise, bright lights, scented stuff, sweating, jokes and make-up.

So used to her self imposed isolation and predictable life is she, that she seems shocked when a new employee Raymond from IT, whom she calls when her computer freezes one morning, initiates conversation with her outside the office, speaking to her as if she might be just like the others.

So used to her self imposed isolation and predictable life is she, that she seems shocked when a new employee Raymond from IT, whom she calls when her computer freezes one morning, initiates conversation with her outside the office, speaking to her as if she might be just like the others. I did find the character of Eleanor a little difficult to believe in, the long years of solitude followed by a relatively sudden transformation seem to occur too easily and quickly, however if I were to suspend judgement on the authenticity of the character and the speed of her life change, which wasn’t hard to do, then it becomes a kind of coming-of-age novel about a young woman overcoming a traumatic past and demonstrates (a little too conveniently) the healing that can come from genuine friendship and being part of a family and community and a functional workplace (if there is such a thing).

I did find the character of Eleanor a little difficult to believe in, the long years of solitude followed by a relatively sudden transformation seem to occur too easily and quickly, however if I were to suspend judgement on the authenticity of the character and the speed of her life change, which wasn’t hard to do, then it becomes a kind of coming-of-age novel about a young woman overcoming a traumatic past and demonstrates (a little too conveniently) the healing that can come from genuine friendship and being part of a family and community and a functional workplace (if there is such a thing).