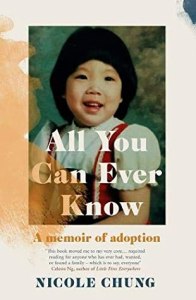

A Memoir of Adoption

While every adoptee’s experience is different, there are so many aspects to the experience and responses to them that resonate with other adoptees, that reading a memoir like this can be very helpful, sharing experiences helps us understand.

While every adoptee’s experience is different, there are so many aspects to the experience and responses to them that resonate with other adoptees, that reading a memoir like this can be very helpful, sharing experiences helps us understand.

And the more there are like this, the more anyone thinking of participating in this practice, might do well to be informed of those varying responses, and to check not just their own motivations, but to do an empathy check; to ask themselves, how might it feel to be the shoes of a child as they become a teenager and an adult, when they come to realise they are not the person you tried to mould.

It’s common for some adoptees to grow up believing they haven’t been affected by the pre-verbal trauma of post-birth separation. At the time the author was born, it was still widely believed, in many western countries at least, that babies were a blank slate, you could mould them into the child you wished for.

Family lore given to us as children has such a hold over us, such staying power. It can form the bedrock of another kind of faith, one to rival any religion, informing our beliefs about ourselves, and our families, and our place in the world. When tiny, traitorous doubts arose, when I felt lost or alone, or confused about all the things I couldn’t know, I told myself that something as noble as my birth parent’s sacrifice demanded my trust. My loyalty.

Love is Colourblind

Her family did have a question, in that they were white Americans of European extraction and their child Korean, though she was born in America. That said, when asked, they were advised by various professionals that race wasn’t an issue. And when it was, she kept it to herself.

I didn’t have the background and the language to call it racism. I’d been led to believe racism was something in the past. Even teachers at school presented racism as a thing we had conquered. It was very well intentioned and wrong. I don’t think I gained perspective on that until I moved away from home and lived in pretty diverse areas on the East Coast.

Nicole Chung shares her experience of being an only child in a caring and loving family, but an over-protective one none the less, holding a subconscious resistance to the idea of their child reconnecting with her biological family.

Photo by Brett Sayles on Pexels.com

It’s an attitude that isn’t about actively preventing them, but about never doing anything to support or facilitate that contact, or conversation, or having sufficient self-awareness to look at defensive responses to the idea and recognise them as unresolved issues.

A classic problem, where the one person you might turn to for support, instead of sympathising, feels threatened and therefore may act in ways that undermine the process, creating trust issues.

An awkward, near impossible dilemma of a child needing an empathetic understanding ear about a subject that is at the core of their being, intersecting with a parent pierced with the reminder of a wound or vulnerability (infertility) making it an unbearable thought, that a child they thought was their own (as if a possession) wants to do something they fear may risk their bond with them.

This may be all you will ever know, I was told. It wasn’t a joyful story through and through, but it was their story, and mine too. The only thing we had ever shared. And as my adoptive parents saw it, the story could have ended no other way.

The Search for Biological Family

Nicole Chung follows the clues she has, and discovers she has a family and siblings, but also discovers information that prevents her from having a complete reunion. The timing of when contact happens coincides with the birth of her first child, an upcoming event that provided a strong motive for searching. Emboldened by the request for medical information, given she was an ailing premature baby herself, the two events move closer and almost collide, becoming too much for her, the roller coaster of setting off down a path of no return.

The contact she does make is ultimately positive, in particular with one of her sisters, she gains a special and close friend, whom she dedicates the book to (and their children). In an interview she talks about the privilege of telling both their stories.

It was honestly a gift. One of the best things I think that’s come out of this book is the chance to talk even more with my sister about it. I just feel really lucky both to have her in my life, and the fact that she really let me — not just let me, but encouraged me to write our story and has been so supportive of it and feels honored by it. – extract from podcast interview, Medium

Photo by Alex Green on Pexels.com

The birth of her daughter also awakens the desire for her to connect with a language and culture that is completely foreign to her. It is a reminder that the next generation born, is not born having been separated and conditioned by the families involved, children are able embrace all, from their perspective it is simple to love family in any shape, form, colour, nationality.

There’s a tendency in adoption still to think that the differences are unimportant compared to the love. And I guess I would just say I think both of those things are really important. And I think if you’re going to look at it realistically — you know — look at the child for the whole person that they are and think about what their experience is going to be. You know, these are conversations that you have to have before you adopt and then, obviously, after, as they age in age-appropriate ways. – extract from podcast interview, Medium

It is a very personal account and kudos to the author for having the courage to share it and inviting readers to go along on the emotional roller coaster of a journey it must have been.

It is a very personal account and kudos to the author for having the courage to share it and inviting readers to go along on the emotional roller coaster of a journey it must have been.

There is a profound sadness in her story though, those aspects of the human story that can’t always be navigated or confronted, understood or forgiven. And so they are judged. And that is the risk and potential source of pain, that taking such a journey involves. Ongoing. The potential for healing.

Since the early 1950s, parents in the United States have adopted more than a half-million children from other countries, with the vast majority of them coming from orphanages in Asia, South America, and, more recently, Africa. South Koreans are the largest group of transracial adoptees in the U.S., and by some estimates, make up 10 percent of the nation’s Korean American population. – Victoria Namkung

Further Reading/Listening

An Extract : Just assimilate Her Into Your Family and You’ll Be Fine by Nicole Chung

Interview with Nicole Chung : ‘I Didn’t Have the Language to Call It Racism’ by Victoria Namkung

No, You Go – A Podcast : Getting Personal with Nicole Chung

Adoption Memoirs Reviewed Here

An Affair With My Mother by Catriona Palmer (Ireland) (2016) (Adoptee)

You Don’t Look Adopted by Anne Heffron (US) (2016) (Adoptee)

Never Stop Walking, A Memoir of Finding Home Across the World by Christina Rickardsson (Sweden/Brazil) (2016) (Adoptee)

Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? by Jeanette Winterson (UK) (2011) (Adoptee)

Red Dust Road by Jackie Kay (Scotland/Nigeria) (2010) (Adoptee)

A Long Way Home (Lion) by Saroo Brierley (Australia/India) (2013) (Adoptee)

Blue Nights by Joan Didion (US) (2011) (Adoptive Parent)

You did a wonderful review of this memoir. I read it a long time ago and was really moved by it, and also saddened. I did have a bit of a problem about how she handled writing about her mother. I felt that the author was still quite young in her life, and that perhaps down the road she might write a second memoir exploring her mother’s life if that is possible. That may be presumptuous of me and it may be she is never inclined to do this, but I felt that perhaps the mom might have had quite a difficult life, which could have explained some of her problematic behavior, and that down the road maybe this could lead to further healing on the author’s part.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that is exactly what I allude to at the end, and it was that which left me with the overall saddened feeling, but I also recognised that the value of the sibling relationship was so important, it became the most important and perhaps sustainable.

I do think that age and numbers of years living in reunion has a lot to do with it. If you read Maya Angelou’s early memoirs and then you read the one she wrote in her eighties, Mom & Me & Mom, we observe how the same author can hold what seem like opposing views.

Whether there is another memoir or another chapter, there is an incomplete chapter in this story of loss and the opportunity not to condone, but to forgive in some way.

LikeLike

That’s so interesting what you’ve noticed about Angelou. You point out how important the sibling relationship was and that is such a good point to make…she did such a good job of writing about that aspect.

LikeLike

By mother, I meant her birth mother, not the mother who adopted her. I got the feeling that the mother had to be held at arm’s length in the mind of the author….which I can understand…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have had no experience of adoption in my own life, or through anyone I know or have known, as far as I know, so this wouldn’t be a book I would bring any experiences to as I was reading. It sounds an interesting read, but not one for the top of the pile at this stage.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This does feel a sad but important read.

LikeLike