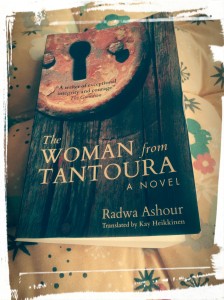

translated by Kay Heikkinen.

Radwa Ashour

Radwa Ashour (1946 – 2014) was a highly acclaimed Egyptian writer and scholar who after studying a BA and MA in Comparative Literature in Cairo, went on to do a PhD in the US in African-American Literature.

As a university student in her native Cairo in the early 1970s, says Ashour, she’d found no one who considered writers in the African diaspora worthy of study. But in 1973, a joyfully-cultivated friendship with Shirley Graham Du Bois world traveler, litterateur, and widow of W.E.B.du Bois led Ashour to UMass. Madame Du Bois, as the école-educated Ashour still calls her late liaison to Amherst, was living in Cairo at the time, and pointed the young Egyptian toward the then-infant Afro-American Studies department here.

Her interest in African-American literature was due to her view that “works on oppression and the overcoming of oppression speak deeply to readers in the Arab world.” She was passionate about social justice, evident in her writing, which sought to personalise the lives and conditions of marginalised groups.

Throughout her career she wrote more than fifteen works of fiction, memoir and criticism, including the novels Granada and Spectres.

The Woman From Tantoura

The more I read, the more this novel got its hooks into me. After a while, a pattern begins to emerge, one that is universal. To find a place where one can live authentically, and be at home.

The more I read, the more this novel got its hooks into me. After a while, a pattern begins to emerge, one that is universal. To find a place where one can live authentically, and be at home.

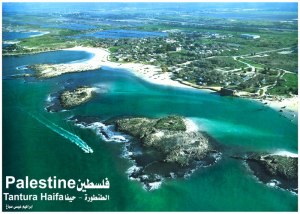

Because of the initial setting, a fishing village in Tantoura, Palestine, in 1948 – the year of ‘The Nakba‘ I expected it was going to be traumatic, it’s the part we don’t wish to linger in, to be witness to the horrific expulsion of families from their homes, of the disappearance of sons and fathers, the rest either becoming refugees in their own country or fleeing to find refuge elsewhere.

Even if we know it can’t begin well, sometimes, we need to read through, to follow the life of a thirteen year old girl into womanhood, in the hope that we see her find solace, to have empathy for her worry and anxiety for her own children and husband after all she has witnessed.

The story begins with Ruqaya standing on the seashore, seeing a young man come out of the sea as if he were of it, as if the waves released him on to land. She is mesmerised. The man will become her fiance, though they will never marry. It is the end of her childhood, the end of blissful days on that shoreline, though memories and the scent of it will stay with her forever, through all the moves that follow. And the key to the old house.

Looking for a Place to Call Home

Photo by Ylanite Koppens on Pexels.com

Later on I would learn that most of the women of the camp carried the keys to their houses, just as my mother did. Some would show them to me as they told me about the villages they came from, and sometimes I would glimpse the end of the cord around their necks, even if I didn’t see the key.

The novel is narrated by her 70-year-old self, pushed into writing down and describing the many experiences and turning points in her life, by her middle son.

It’s not only the story I’m interested in, I’m after the voice, because I know its value and I want others to have the chance to hear it.

A reluctant narrator, the timeline moves back and forth, less a chronology events than a response to emotions that arise that provoke the memory. It’s a recollection of a life lived in the wake of tragedy, of determination and survival, of not forgetting, maintaining a connection to a culture and values as best one can.

There was no acceptable or reasonable answer for the question for “why?” however much it rose up, loud and insistent. I did not ask “why”. I mean I didn’t ask the word, and perhaps I was not conscious that it was there, echoing in my breast morning and evening and throughout the day and night. I didn’t say a thing; I fortified myself in silence.

While her mother uses imagination to create a vision of what happened and where the missing are, Ruqayya’s advances then retreats, as the present awakens the past, rarely does she dwell in an idealised future.

While her mother uses imagination to create a vision of what happened and where the missing are, Ruqayya’s advances then retreats, as the present awakens the past, rarely does she dwell in an idealised future.

Am I really telling the story of my life or am I leaping away? Can a person tell the story of his life, can he summon up all its details? It might be more like descending into a mine in the belly of the earth, a mine that must be dug first before anyone can go down into it.Is any individual, however strong or energetic, capable of digging a mine with their own two hands?

Seeking Refuge

To see them seek refuge in another country, where a similar tragedy can happen, one understands what it must feel like to feel that no place is safe, and then when she finds a ‘safe place’ with her high achieving son, the culture shock is too much to bear, bringing to mind the memoir of the Palestinian intellectual Edward Said’s Out of Place.

There is no place that quite replaces the childhood environment and home, except perhaps to create one’s own family, and this Raqayya will do, with her son’s and the daughter, a girl Maryam her husband brings home one day from the hospital, adopting her as their own. And in growing things, not the almond tree or the olives, but flowers, a thing of beauty, the damask rose, the bird of paradise.

There is no place that quite replaces the childhood environment and home, except perhaps to create one’s own family, and this Raqayya will do, with her son’s and the daughter, a girl Maryam her husband brings home one day from the hospital, adopting her as their own. And in growing things, not the almond tree or the olives, but flowers, a thing of beauty, the damask rose, the bird of paradise.

I found similarities in reading this novel, to the feeling evoked in reading Nella Larsen’s Quicksand, her constant search too, for the place where she could be herself, though her search was all the more elusive and complex, there being no place or people who accepted her rootlessness, her mixed blood, something that the clannishness of many ‘peoples’ reject.

“In Egypt, we have a flag, an airline of our own, we are an independent country,” she said. “But there is this feeling we are not free to be who we are in the new world order.” I am always conscious I’m a person from the Third World. I’m an Egyptian, an Arab, and an African all in one. Also, I’m a woman. I know to be all these things is to be particularly conscious of constraint.” Radwa Ashour

The Woman From Tantoura is my first read for #WITMonth, reading Women in Translation.

The damask rose.

LikeLike

There it is again!

LikeLike

This sounds excellent … this is what’s so good about WIT Month, it brings to our attention books we might never have heard of otherwise.

LikeLiked by 2 people

An important message.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, and a universal one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed reading this novel, too. Thanks for reviewing it. -Neri

LikeLike

It was such an absorbing read, and interesting the way it slowly changes toward the end without even realising it’s crept up and into the reader’s psyche. It’s like once we know they’re really safe it’s ok for the release of emotion to come.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a universal longing…a place to call home and to feel accepted. Lovely review.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kind and thoughtful words Carmel.

LikeLike

I was pleased to see another review of this novel. I reviewed it on Bookword blog last year, and recommended it on Woman’s Hour too. It’s a strong story, and a very authentic narration I think. I will be including it as one of my choices for #WITMonth as well.

LikeLike

I’ve wanted to read her work for a while and knew this one was going to be special. I thought it was excellent, yes, it felt so authentic, her empathy, it’s like she was that woman, it felt like a real story, I’m sure it’s been inspired by many that she met throughout her life.

I have Spectres and Granada still to read and look forward to those too.

LikeLike

I’ve not heard of this author and I’d be really interested to read this. Ideas around home are so powerful, and as you say, its a universal concern.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really want to read this after reading your thoughtful review.. What a great idea this #WIT month is.

LikeLike

Hi Claire 🌺

I am re-reading ” THE WOMAN FROM TANTOURA ” I hope readers will pick up this MUST READ to perhaps understand the horror happening in Palestine and to Palestinians.

LikeLiked by 1 person