When I look back at my absolute favourite book of the year in recent years, there is a common theme running in which an author has written a story that comes from deep within their cultural heritage; it’s there in my favourite book of 2017 Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi, a book that reaches back to the author’s Ghanaian heritage, in Simone Schwartz-Bart’s The Bridge of Beyond and in Jamaica Kincaid’s The Autobiography of My Mother. It’s even there in Eowyn Ivey’s The Snow Child.

This is what appealed to me immediately about the prospect of reading Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu. It promises to do the same thing, to take the reader from where we are at today in a culture and link it back to the past, from modern day Uganda to the era of when the region was ruled as a kingdom. And it succeeds brilliantly, in a way rarely seen in literature in the UK/US published today.

This is what appealed to me immediately about the prospect of reading Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu. It promises to do the same thing, to take the reader from where we are at today in a culture and link it back to the past, from modern day Uganda to the era of when the region was ruled as a kingdom. And it succeeds brilliantly, in a way rarely seen in literature in the UK/US published today.

Kintu was discovered when a project called Kwani? launched a manuscript competition in 2012 to discover the best unpublished novels by writers from across Africa, and to publish them for readers there. Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s excellent Stay With Me, was one of seven manuscripts shortlisted, it also went on to make the shortlist of the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2017.

About the Kwani? project, one of the judges, Ellah Wakatama Allfrey said:

What we looked for as judges were manuscripts that told stories from the inside without the burden of focusing on how an imagined ‘West’ would view them.

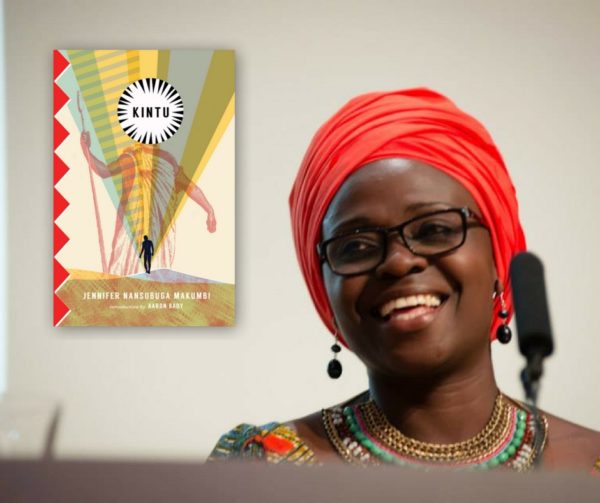

As a result of winning that prize Kintu was published by Kwani Trust (in Kenya) before being offered to international publishers. It was published in the US (Transit Books) and the UK (One World Publications) and in March 2018 Jennifer Makumbi learned she was a recipient of a prestigious Windham Campbell Prize for Literature worth US$165,000. She is working on her second novel.

My Review:

1750 Buddu Province, Buganda

Kintu is the name of a clan, the original clan elder Kintu Kidda fell in love with Nnakato, an identical twin (the younger) and her family refuse to allow him to marry her unless he married her sister Babirye first. He refused. They resisted. He relented.

Kintu’s mind lingered on the primal conflict that led to a soul splitting into twins. No matter how he looked at it, life was tragic. If the soul is at conflict even at this remotest level of existence, what chance do communities have? This made the Ganda custom of marrying female identical twins to the same man preposterous. It goes against their very nature, Kintu thought. Twins split because they cannot be one, why keep them as such in life? Besides, identical men did not marry the same woman.

Babirye gave him four sets of twins while Nnakato was unable to conceive. When the twins, raised as if they belonged to Nnakto were adults, Nnakato finally gave birth to a son Baale. They adopted a baby boy Kalema, from Ntwire a widower who was passing through their lands, who decided to stay in gratitude to Kintu and Nnakto for raising his son in their family.

When tragedy occurs, Kintu tries to conceal it, Ntwire suspects something and places a curse on Kintu, his family and their future descendants.

The novel is structured into Book One to Book Six, the first five books focus on different strands of the Kintu clan, the first book being the original story of Kintu Kidda and his family in the 1700’s (pre-colonial era) and the latter stories are set in modern times, colonial interlopers have left their imprint, however this is not their story nor a story of their influence, except to note the impact on the kingdom.

After independence, Uganda – a European artefact – was still forming as a country rather than a kingdom in the minds of ordinary Gandas. They were lulled by the fact that Kabuku Mutees II was made president of the new Uganda. Nonetheless, most of them felt that ‘Uganda’ should remain a kingdom for the Ganda under their kubuka so that things would go back to the way they were before Europeans came. Uganda was a patchwork of fifty or so tribes. The Ganda did not want it. The union of tribes brought no apparent advantage to them apart from a deluge of immigrants from wherever, coming to Kampala to take their land. Meanwhile, the other fifty or so tribes looked on flabbergasted as the British drew borders and told them that they were now Ugandans. Their histories, cultures and identities were overwritten by the mispronounced name of an insufferably haughty tribe propped above them. But to the Ganda, the reality of Uganda as opposed to Buganda only sank in when, after independence, Obote overran the kabuka’s lubiri with tanks, exiling Muteesa and banning all kingdoms. The desecration of their kingdom by foreigners paralysed the Ganda for decades.

Each beginning of the six parts/books however narrates over a few pages, something of the story of a man named Kamu Kintu, who is seized from his home, hands tied behind his back and taken away for questioning by a group of local councillors. Overhearing someone mutter the word thief, an angry mob of villagers menace him without knowledge of the reason for his being detained and he is killed, left for dead on the road, the men who’d requested he come with them fleeing. What subsequently happens to every one of those councillors is equally mysterious, creating a thread of mystery that both links and separates the family stories that make up the novel.

We don’t find out who Kamu Kintu is or how he is connected to the families we encounter in each part, until Book Six, where the threads that tie the clan together begin to connect in the enthralling homecoming.

Throughout each family and over the years certain aspects replicate throughout the families, the presence of twins, premature death, as if the curse that was muttered so long ago continues to reverberate through each generation. Some of them are aware of the curse, remembering the story told by their grandmothers, others haven’t been told the truth of their origins, in the hope that ignorance might absolve them.

Her grandmother’s story had intruded on her again. All day at work, the story, like an incessant song, had kept coming and going. Now that she was on her way home, Suubi gave in and her grandmother’s voice flooded her mind.

Some are haunted by ghosts of the past, thinking themselves not of sound mind, particularly when aspects of their childhood have been hidden from them, some have prophetic dreams, some have had a foreign university education and try to sever their connections to the old ways, though continue to be haunted by omens and symbols, making it difficult to ignore what they feel within themselves, that their mind wishes to reject. Some turn to God and the Awakened, looking for salvation in newly acquired religions.

Some are haunted by ghosts of the past, thinking themselves not of sound mind, particularly when aspects of their childhood have been hidden from them, some have prophetic dreams, some have had a foreign university education and try to sever their connections to the old ways, though continue to be haunted by omens and symbols, making it difficult to ignore what they feel within themselves, that their mind wishes to reject. Some turn to God and the Awakened, looking for salvation in newly acquired religions.

It’s brilliant. We traverse through the lives of these families, witness their growth, development, sadness’ and joys, weaving threads of their connections together, that will eventually intersect and come to be understood and embraced by all as the clan is brought together to try to resolve the burden of the long-held curse that may have cast its long shadow over this clan for so many generations.

One of the things that’s particularly unique about the novel, is the contrast of the historical era, 1750’s with the modern era, the historical part shows the unique way of life before the arrival of Europeans, in all its richness and detail, how they live, the power structures, the preparation for the long journey to acknowledge a new leader, the protocols they must adhere to, the landscapes they traverse. An article in The Guardian notes twin historical omissions and concludes that the novel is the better for it:

Makumbi mostly avoids describing both the colonial period, which so often seems the obligation of the historical African novel, and Idi Amin’s reign, which seems the obligation of the Ugandan novel. Kintu is better for not retreading this worn ground.

It reminded me of the world recreated by the Guadeloupean-French-African writer, Maryse Condé, in her epic historical novel Segu, another African masterpiece, set in the 1700’s in the kingdom of Segu.

I hope the success of Kintu encourages other young writers from within the vast storytelling traditions of the many African countries to continue to tell their stories and that international publishers continue to make them available to the wider reading public, who are indeed interested in these lives, cultures, histories and belief systems of old that continue to resonate in the modern-day, despite political policies and power regimes that seem to want to change them.

Further Reading

Brittle Paper: Essay – When We Talk about Kintu by Ellah Wakatama Allfrey

Africa In Words: Review – Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s ‘Kintu’ Made Me Want to Tell Our Stories by Nyana Kakoma

The East African: Article – Kintu’s ‘Africaness’ pays off for Jennifer Makumbi by Bamutaraki Musinguzi

The Guardian: Kintu by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi review – is this ‘the great Ugandan novel’? by Lesley Nneka Arimah

Buy a copy of Kintu via BookDepository

Note: Thank you to the UK Publisher One World Publications for sending me a copy of the book.

I couldn’t resist, I had to read your review. I was hoping to spoil myself a little, but this is so well written that you’ve managed to say exactly what the story is about without revealing too much.

I liked that the novel avoids describing the colonial period, but I found it interesting of myself that as I read the sections set in the past, I kept expecting some reference or inclusion of the colonial period. I noticed its absence, but I didn’t miss it/didn’t think the book was lacking for not including it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much for reading the review, I would totally understand if you felt you needed to wait, it was so great to chat with you yesterday, to find another reader reading it at the same time as me. I try to be careful not to spoil any of the surprises for readers, while still making it interesting enough to entice those who haven’t read it yet to pick it up.

I didn’t want to overanalyse the discussion about the omission of the colonial period, because it’s so great to read the book without having to be aware of that and it’s what makes Maryse Condé’s Segu so wonderful as well, it shows us a culture in a time when it was growing and evolving based on nearby influences around it, and then the sons set out on their adventures and come across those other foreign influences.

Kintu sticks to its premise, to show how more traditional influences continue to manifest across the generations, they refer to it as a curse, other cultures call it karma, still others unhealed trauma, and today its even said to be imprinted in our DNA.

I can’t wait to see what her next novel will be about. Happy Reading!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I enjoyed our chat too. 🙂

And I like that by not focusing on the omission of the colonial period in your review, you show respect for what the novel is trying to do. I like that a lot.

I’d also be interested in reading another book by her…when I’m done with this one, of course.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Claire, my tbr list is peppered with recommendations from you at the moment! And they are generally books that I suspect I would never have stumbled across on my own. Another one for the list here – thank you!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I don’t if I should apologise or say Yay! I guess Yay, I know I like to have a TBR I’m looking forward to and there have been a lot of good recommendations recently, and I’ve been reading a little more than usual over winter, I think that’s going to slow down with Spring approaching! But Kintu really is unique, I don’t see anything else like it on the horizon for 2018, but I’ll be keeping an eye out and I’m sure there’ll be some older titles that have been missed to resurrect. Happy Reading Sandra.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Claire, I’ve purchased this as a gift for my niece who married a young man from Uganda. But – I can’t give it to her until I read it myself!! I’ll try to keep it nice – and if I can’t, I’ll just have to buy another copy for Glenna & Henry. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful gift Debbie and yes, you absolutely must read it too! The review already was so long, so I didn’t mention it, but since you have a connection to Uganda I’ll share it with you, I wanted to say that one of my favourite films I’ve seen recently (and I don’t see many films) was set in Uganda and based on a true story, it’s called Queen of Katwe directed by Mira Nair. Have you seen it or heard of it? It’s a wonderful film and because I’d seen it, it made imagining some of the scenes that much easier.

There’s a wonderful soundtrack too I’ll link it here, I’m sure you’ll enjoy watching/listening to it:

Number One Spice

LikeLike

This sounds like an excellent epic novel, doing for Uganda what Homegoing did for Ghana. I am surprised I haven’t heard more about it — yours and Lonesome Reader’s are the only two blog reviews I recall seeing. I do hope my library system will order a copy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really was expecting this title to make the Women’s Prize for Fiction long list, just as I was last year for Homegoing, I don’t know why these titles seem to slip under the radar, they’re both incredible books. Well Kintu did win the Windham Campbell award, which is brilliant for the author, and good to know she’s working on her next novel, she’s an excellent writer and an engaging storyteller and I just love the originality, sticking to her storytelling tradition and imagining the Kingdom before the arrival of Europeans.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Claire, you manage to find such rich reads, thank you! Like Sandra, I have all sorts of recommendations from you in my TBR list – and here’s another treasure. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is indeed a treasure Liz, sorry to topple your pile, there are always so many good reads at the beginning of the year, reading other bloggers favourites and finding gems like this one, a novel that has had a long incubation period.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent review, Claire, as always. 🙂 I read Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing and I have still not recovered from its profound impact. Never have I felt so moved by a book telling the history of my own people. I’m sure I’m going to be equally moved by Kintu. I will certainly look for a copy and buy. Thanks for the review. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent review and yet another book to add to the wishlist, your recent Booker Prize longlist post introduced em to a lot of new books and Frankenstein in Baghdad is on the pile, waiting its turn.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Women’s Prize for Fiction Shortlist 2018 #WomensPrize – Word by Word

Pingback: Top Reads of 2018 – Word by Word

Pingback: Kintu by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi – Jill's Scene

Pingback: Zuleikha by Guzel Yakhina (Russia) tr. Lisa Hayden – Word by Word

Pingback: Women’s Prize for Fiction Winner 2019 – An American Marriage by Tayari Jones – Word by Word

Pingback: The First Woman by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi – Word by Word

Pingback: Best Books Read in 2021 Part 2: Top 10 Fiction – Word by Word

A great review, and I also made a mental connection between this book and Condé’s Segu. I tried getting into Kintu twice, but unsuccessfully, perhaps I should try again. Your review is certainly very inspiring.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kintu was great, it was my top read of that year, and I enjoyed her next novel as well, The First Woman. I think they are stories not to set aside too long, to stay with them. Condé is one of my favourite authors, we are fortunate to have much of her work available in English. Thanks for visiting Diana.

LikeLiked by 1 person