A fabulous collections of correspondence and essay like responses to interview questions over a period of twenty-five years since the publication of her first novel Troubling Love.

The title ‘Frantumaglia‘, a fabulous word left to her by her mother, in her Neapolitan dialect, a word she used to describe how she felt when racked by contradictory sensations that were tearing her apart.

The title ‘Frantumaglia‘, a fabulous word left to her by her mother, in her Neapolitan dialect, a word she used to describe how she felt when racked by contradictory sensations that were tearing her apart.

She said that inside her she had a frantumaglia, a jumble of fragments. The frantumaglia depressed her. Sometimes it made her dizzy, sometimes it made her mouth taste like iron. It was the word for a disquiet not otherwise definable, it referred to a miscellaneous crowd of things in her head, debris in a muddy water of the brain. The frantumaglia was mysterious, it provoked mysterious actions, it was the source of all suffering not traceable to a single obvious cause…Often it made her weep, and since childhood the word has stayed in my mind to describe, in particular, a sudden fit of weeping for no evident reason: frantumaglia tears.

And so for her characters, this is what suffering is, looking onto the frantumaglia, the jumble of fragments inside.

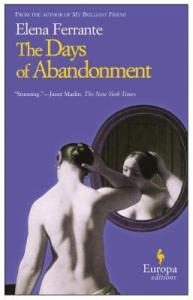

The first half chiefly concerns communication around Troubling Love and The Days of Abandonment, the latter written ten years after her debut, although other stories were written in between but never published, the author not happy with them as she so piercingly reveals:

The first half chiefly concerns communication around Troubling Love and The Days of Abandonment, the latter written ten years after her debut, although other stories were written in between but never published, the author not happy with them as she so piercingly reveals:

I haven’t written two books in ten years, I’ve written and rewritten many. But Troubling Love and The Days of Abandonment seemed to me the ones that most decisively stuck a finger in certain wounds I have that are still infected, and did so without keeping a safe distance. At other times, I’ve written about clean or happily healed wounds with the obligatory detachment and the right words. But then I discovered that is not my path.

The second half implies a delay in the publication of the collection to include interviews and question-responses around the Neapolitan Quartet, beginning with the renowned My Brilliant Friend.

Readers ask poignant questions, while the media tend to obsess about her decision to remain absent (as opposed to anonymous) from promotional activity, to which she has many responses, one here in a letter to the journalist Goffredo Fofi:

In my experience, the difficulty-pleasure of writing touches every point of the body. When you’ve finished the book, it’s as if your innermost self had been ransacked, and all you want is to regain distance, return to being whole. I’ve discovered, by publishing, that there is a certain relief in the fact that the moment the text becomes a printed book it goes elsewhere. Before, it was the text that was pestering me; now I’d have to run after it. I decided not to.

Perhaps the old myths about inspiration spoke at least one truth: when one makes a creative work, one is inhabited by others-in some measure one becomes another. But when one stops writing one becomes oneself again.

…I wrote my book to free myself from it, not to be its prisoner.

She shares her literary influences (works of literature about abandoned women) from classic Greek myths, Ariadne to Medea, Dido to the more contemporary Simone de Beauvoir’s The Woman Destroyed, referring to recurring themes of abandonment, separation and struggle. She mentions literary favourites, Elsa Morante’s House of Liars.

One interviewer asks why in her early novels, her characters depict women who suffer, to which she responds:

The suffering of Delia, Olga, Leda is the result of disappointment. What they expected from life – they are women who sought to break with the tradition of their mothers and grandmothers – does not arrive. Old ghosts arrive instead, the same ones with whom the women of the past had to reckon. The difference is that these women don’t submit to them passively. Instead, they fight, and they cope. They don’t win, but they simply come to an agreement with their own expectations and find new equilibriums. I feel them not as women who are suffering but as women who are struggling.

And on comparing Olga to Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina, who she sees as descendants of Dido and Medea, though they have lost the obscure force that pushed those heroines of the ancient world to such brutal forms of resistance and revenge, they instead experience their abandonment as a punishment for their sins.

Olga, on the other hand, is an educated woman of today, influenced by the battle against the patriarchy. She knows what can happen to her and tries not to be destroyed by abandonment. Hers is the story of how she resists, of how she touches bottom and returns, of how abandonment changes her without annihilating her.

In an interview, Stefania Scateni from the publication l’Unità, refers to Olga, the protagonist of The Days of Abandonment as destroyed by one love, seeking another with her neighbour. He asks what Ferrante thinks of love.

In an interview, Stefania Scateni from the publication l’Unità, refers to Olga, the protagonist of The Days of Abandonment as destroyed by one love, seeking another with her neighbour. He asks what Ferrante thinks of love.

The need for love is the central experience of our existence. However foolish it may seem, we feel truly alive only when we have an arrow in our side and that we drag around night and day, everywhere we go. The need for love sweeps away every other need and, on the other hand, motivates all our actions.

She again refers to the Greek classics, to Book 4 of the Aeneid, where the construction of Carthage stops when Dido falls in love.

Individuals and cities without love are a danger to themselves and others.

The correspondence with the Director of Troubling Love (L’amore molesto), Mario Martone is illuminating, to read of Ferrante’s humble hesitancy in contributing to a form she confessed to know nothing about, followed by her exemplary input to the process and finally the unsent letter, many months later when she finally saw the film and was so affected by what he had created. It makes me want to read her debut novel and watch the original cult film now.

The correspondence with the Director of Troubling Love (L’amore molesto), Mario Martone is illuminating, to read of Ferrante’s humble hesitancy in contributing to a form she confessed to know nothing about, followed by her exemplary input to the process and finally the unsent letter, many months later when she finally saw the film and was so affected by what he had created. It makes me want to read her debut novel and watch the original cult film now.

Frantumagli is an excellent accompaniment to the novels of Elena Ferrante and insight into this writer’s journey and process, in particular the inspiration behind her characters, settings and recurring themes.

Note: Thank you to the publisher Europa Editions, for providing me a copy of this beautiful book.

This sounds fascinating. I’ve had the book on my shelf for a while and really look forward to reading it, along with her earlier novels. Thanks for this great review.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I realise I haven’t seen many reviews of this collection, yet many appear to be aware of it, I think I was just waiting for the right time and inspiration to delve into it, and after reading Domenico Starnone’s response to The Days of Abandonment, I did so, perfect timing as it happens. I do hope she continues to publish, her work comes from such an interesting inner space and perspective.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sounds like a very compelling read, Claire – the references to Greek classics are particularly interesting. I didn’t take to Troubling Love when I tried to read it a year or so ago, so I’ll be curious to see what you make of it when the time comes. Maybe my timing was off, sometimes it’s hard to tell!

LikeLike

Yes, it was interesting to read her own reaction to the film that was made of it, quite shocking, as if seeing it for what it really was and disbelieving that she could have created something that was perceived in that way, there’s kind of a safety behind words that is made transparent by the visual.

I’ve started with her more recent works and then last summer read The Days of Abandonment which was stunning and so alive and vulnerable and I was reminded of it immediately when I read Domenico Starnone’s Ties this week, clearly there’s a connection between the two works, if not between the writers. It compelled me to reach for this work, to understand more of why I felt Ferrante’s work to be that much more alive to provoke such a different reaction to that which Starnone manifested in me.

Troubling Love now for me, will be seen in the context of those influences I now know of, and it was the debut novel, interesting that she didn’t anything for ten years following that, despite having written other books, I’m sure her publisher would love to get a look those she rejected herself.

LikeLike

Ferrante is such an interesting writer, there’s an uninhibitedness to her writing which is compelling and disturbing at the same time and which is perhaps connected to her desire to remain out of the spotlight, as perhaps the anonymity creates a space in which she can allow her writing to flow. I’m both fascinated by and wary of reading her essays, partly because it seems to step out of the realms of fiction into the facts of her life (though perhaps that is just an illusion) and also because I think they will leave me wanting more of her writing, to know more, to explore more of the woman behind the books. But the connection she makes with Greek mythology is fascinating and her writing remains beautiful as always. Wonderful review Claire.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I trust Elena Ferrante with what she publishes, because she has given more thought to the boundaries than any other writer, as she says over and again, she isn’t anonymous, she is merely absent from the promotional machine that would put her in front of the media. She is happy to discuss literature and writing for those who are interested, who tend to be readers, the issue of her identity has really only become obsessional since the Neapolitan quartet became an international bestseller.

The first part of the book focusing on the first two books wrote is more interesting because it talks more about the inspiration behind what she created and her shoch at being confronted it on screen for example, so deep into her writing does she go, that to see it like that from the outside was shocking. I read this as a reader who likes to write and I think she is an interesting example of someone who writes as she heals and she clearly has a lot in her life experience to heal from, but sometimes the rawness of the fiction can be more appreciated by being given some insight into the inspiration behind the authors intention. I think she encourages us to be brave by her example, but she has taken a necessary precaution, knowing what it is she is uncovering. She has also made an important pact with her own family to protect them.

I don’t feel this crosses over the bounds of her private life, because she has had control over the output and volunteers these insights to prove that it is possible to have a serious literary conversation without having to divulge irrelevant details of ones private life. I find her work very daring and could do with a bit of encouragement in that direction, ultimately we follow our instinct and I’m glad ine lead me to read this, especially after having read Starnone’s response to The Days of Abandonment.

LikeLike

Interesting that this academic work is being presented today, they articulate so much better than I ever could, what it is about Elena Ferrante that makes you want to know about her work, not her person. It might be too academic for me, but I’m intrigued to read it!

Elena Ferrante’s “Smarginatura” and the Identity of Women

Interview with Grace Russo Bullaro, co-author of “The Works of Elena Ferrante. Reconfiguring the Margins”

LikeLike

The ransacking of the self – that is a great expression to describe what it is like to write.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And Elena Ferrante does so extremely effectively, I found it interesting that she allowed those first two books to be published, referring to them as wounds that still require healing, allowing her to pierce them further or ‘ransack’ them in order to serve her creative expression, her art, yet those that have happly healed and from which she maintains a distance, she held back and they have not been shared with her publisher. That I am still thinking about, the rawness of vulnerability versus the perhaps overcookedness of control.

LikeLike

Claire – I love the quotes you selected. I am almost more intrigued to read Frantumaglia before any of the Elena Ferrante novels [that have been waiting ever-so-patiently for me in my bookshelves].

LikeLiked by 1 person

She is such an interesting thinker and her portrayal of issues regarding women is so visceral, it almost doesn’t surprise me to learn that the books she’s chosen to publish are those where the wound has yet to heal completely. Reading Frantumaglia, made me wish I’d read her work in chronological order, to witness the growth.

She’s a relatively new name to most, but this has been a long journey, both living it and writing through it clearly.

Thank you for your thoughtful comment Leslie, I totally understand your reasoning. The only thing that lets it down sadly, are the relentless questions from the media following publication of the Neapolitan novels with regard to her identity, there is so much more richness to her intellect and understanding of humanity and this obsession with her identity feels quite small minded in comparison.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Claire – “the richness to her intellect and understanding of humanity” is what you’ve been able to convey with your review; and that’s what I’m interested to explore.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Reading Women in Translation #WITMonth – Word by Word

Pingback: A Catalog of Birds by Laura Harrington – Word by Word

Pingback: Troubling Love by Elena Ferrante – Word by Word

Pingback: Elena Ferrante Shares 40 Favourite Books by Female Authors – Word by Word

Pingback: The Lying Life of Adults by Elena Ferrante translated Ann Goldstein – Word by Word